Connecting Content to the World Outside the Classroom in Hybrid Classes

Published in:

November 19–20, 2020

Virtual Symposium

Once upon a time, there was … an introduction

Once upon a time, there was an undergraduate student at the University of Florence, in Italy, who wanted to study languages to be able to travel the world and to meet people from different countries and cultures. Back then, she had no clear idea of what she could do with a Russian (and French) degree, but she had learned from a very young age that traveling and appreciating literature and the arts were as important as a job, whatever this might end up being. Her parents thought this, too, which is why they “dragged” her throughout Europe and its museums in a camper every summer of her first fifteen years of life. As an only child those trips were not as exciting as going to the beach with her friends, yet the little girl learned how to expand her boundaries, appreciate diversity, and respect those who were different from her. She also learned how to ask for “la cuenta, por favor,” although her parents did not know any language beyond Italian (instead relying on gestures, as Italians are famous for). As a result, the girl decided to learn languages once she enrolled in a university.

Many years later, as a college professor, when she looked back at her undergraduate years, the now grown-up girl realized that much of the content that she had sweated over, preparing for her written and oral exams, was almost gone, as if she had never learned it, except for a couple of courses in glottology and Slavic linguistics. Nevertheless, all the books and other materials were still there, occupying her old bookshelves in her mother’s residence in Tuscany. In that summer of 2020, during a global pandemic, my mother—yes, I am the little girl who traveled throughout Europe during her childhood and adolescence—was preparing to move to a new apartment (fabulous timing during a pandemic, I agree), and via WhatsApp she sent me an incredible number of pictures documenting the instruments of my undergraduate education: books, notes, and syllabi of a life of study that was almost forgotten. In that summer of 2020, I finally realized that I would need to change something if I wanted my students to graduate from college with not only a degree, but with something that would accompany them on their life’s journey. .

While everything began in Florence, the global pandemic that prevented me from flying to Italy and being with my mother during a major move was the event that eventually spurred me to recognize the necessity for making a change in my hybrid film classes. As a result, I enhanced the critical and creative thinking required in these classes, while incorporating cultural competencies with the goal of actively connecting the classroom (virtual and actual) to the world outside of it, through a process that I call connections.

To provide some background, at Farmingdale State College, I mostly teach upper-level courses fulfilling the general education requirements for the arts and humanities to non-majors. This may remind you of the crisis of the humanities (Ahlburg, 2019; Bivens-Tatum, 2010; Plumb, 1964; Schmidt, 2018a; Schmidt, 2018b), which I have indeed investigated in one of my publications, exploring how we could make the humanities and the arts, especially in relation to language teaching, as valuable as the STEM courses at our institutions (De Santi, 2020b, pp. 32-37). The courses I teach include Italian Cinema, International Cinema, Italian Food Culture and History, and Italian Culture and Civilization, as well as Italian language classes, in face-to-face (f2f), hybrid (50% online and 50% in the classroom, or remotely during the COVID-19 pandemic), and fully online modalities. Though these classes needed a change, you can understand that I could not revise them all at once. Certainly, when I considered how to make a change, my dilemma was not Shakespearean (“To be, or not to be”), because it was not a matter of the life or death of these courses. Instead, it was mostly a question of what road to take to give students something more than mere content. I had a couple of questions that I needed to answer:

- How can I make the course a valuable experience while teaching content?

- What can I use to engage students in an online environment?

- What will students retain after graduation?

Each of us might have different dilemmas and questions to answer, and if you, dear reader, want to reflect on yours, we can take this journey together. But let’s begin with my questions and see how I responded to them.

How can I make the course a valuable experience while teaching content?

In my almost fifteen years as a college teacher—in a career that has seen me passing from teaching assistant, adjunct, lecturer, to assistant professor—I have always travelled in the same direction, though without conscious pedagogical consideration. I have always wanted to offer my students more than content, but I was not sure how to accomplish this. The idea of giving them an experience surfaced early, but it did not become concrete until I taught a course in Italian food culture at my previous institution, where the students were taught in the kitchen of a residence hall and had a lasting experience that many characterized as a “blast” (see the website Italian Food Culture in Practice as cited in the bibliography). This experience is more fully recounted in a previous essay (De Santi, 2018a). In another article, where I explored further implications of such a teaching approach, I pedagogically situated the teaching of Italian language and culture through food within the theoretical framework of learning by doing (De Santi, 2018c). In fact, my decision back then, and now, was certainly sustained by a methodological approach that springs from task-based instruction (TBI) (Brandl, 2008, pp. 5-22; Larsen-Freeman and Anderson, 2011, pp. 115-130, 149-163), the core idea of which is the above-mentioned learning by doing (Brandl, 2008, p. 12). This approach has given me the pedagogical foundation to adapt learning by doing into learning by connecting, a way of learning through creating connections and making students agents of their own learning.

Nevertheless, before making changes, it was important for me to give the students practical tools they could use to start their journey. First, for my classes in International Cinema and Italian Cinema, I adopted an Open Education Resources (OER) textbook of film studies (Sharman, 2020). The decision was not only ethically based, namely to provide students with a textbook at no cost, but it was also content-based, because the textbook reaches students through accessible language supported by short videos that appeal to visual learners. At the end of the fall of 2020, students agreed that Sharman’s textbook works wonderfully and should not be replaced with anything else. Second, in addition to the OER textbook, I also included excerpts from academic sources—where scholarly analysis is provided—to expose students to texts beyond pre-digested analysis.

While readings are an essential part of students’ learning process, we might agree that alone they are not enough. For this reason, all four of my courses now fulfill the requirements for applied learning (AL) at my institution, two for civic engagement and two for undergraduate research. Both the International Cinema and Italian Cinema classes are COIL (Collaborative Online International Learning) courses that have been COILed with Italy, Japan, Mexico, and South Africa, in collaboration with colleagues teaching visual studies, mathematics, archeology, environmental studies, English as a Second Language (ESL), and architecture (a brief delineation of the fall 2019 COIL experience can be found in De Santi, 2020b, pp. 43-44). For those unfamiliar with COIL:

Collaborative Online International Learning (COIL) is an approach that brings students and professors together across cultures to learn, discuss and collaborate as part of their class. Professors partner to design the experience, and students partner to complete the designed activities. COIL becomes part of the class, enabling all students to have a significant intercultural experience within their course of study. (What Is COIL?)

As civic engagement, COIL is certainly ideal for fostering connections. It connects content to the world outside the classroom to make a valuable, lasting experience for the students, and is especially effective when fostering cultural competencies. However, cultural perspectives could also be fostered through other channels beyond the classroom, with the goal of engaging students with their own learning, for which, as instructors, we are only the mediators. For this purpose, the next section investigates how I have engaged students in an online, hybrid environment, which has become a key question for many during the 2020-2021 global pandemic.

What can one use to engage students in an online environment?

The engagement of students in an online environment is an issue that many of us teachers have been dealing with in both normal and pandemic times (for a reflection on teaching online during the COVID-19 pandemic, see De Santi, 2020a). Reflecting upon what you have done in the months during which we were rapidly ushered into a world of remote teaching and learning, you may recognize what worked and what didn’t. Certainly, every class, every teacher, every situation, institution, discipline, and student body are unique, and what I share with you, dear reader, is what I have done, which is not the perfect recipe, but it is working for my courses and my students (and for me as an instructor).

To contextualize my approach, I will first discuss the technological environment that frames my courses. My hybrid (and online) classes are run through the learning management system (LMS) of Blackboard, where all the students’ interactions occur. During the pandemic, the remote components of my hybrid classes have taken place in Google Meet (though it could have equally been Collaborate Ultra in Blackboard or Microsoft Teams), while most of my digital projects are created through Screencast-O-Matic, a screen recorder software that I first introduced in my language classes several years ago (De Santi, 2018b). My international collaborations (COIL) have been run through Microsoft Teams or Google Drive, and I have used Padlet for ice-breaker activities.

While this is my technological environment, perhaps you want to know what the students are required to do on a weekly basis to engage with the class. This is what I call Engagement 1.0: students have to write a 200-word reaction paper on the assigned readings and a 200-word discussion board post on films, videoclips, or excerpts from primary sources. On the discussion board, students must also reply to at least two other students and to those who reply to them. As my syllabus states, “A reply involves more than just saying ‘that is very interesting.’ Students are asked to comment on why they agree with something, or to add something new that is relevant and relates to what their classmates wrote.”

Throughout the semester, students must also complete projects, and I can offer two examples, including: (1) applied learning projects accomplished through interviewing Italian American or Italian diaspora community members, and which result in a 1,000-word narrative as well as a digital presentation to the class, and also requires students to comment on other students’ projects; and (2) COIL projects, in most cases digital storytelling video project collaborations by groups of students from different institutions.

Despite these innovations intended to engage students and give them a life experience to remember (and hopefully cherish) well after graduation, some students seem not to engage as much as I would wish, and this brings me to my last question about the retention of what they study after graduation.

What will students retain after graduation?

Think of your courses: What will students remember about them after graduation? It is an important question. Thinking back to your own undergraduate years, what do you remember of the classes that you took? As you know, I was not happy when I confronted my own response to this question, so I redesigned the weekly discussion boards where connections became a key emphasis.

In my hybrid film classes, I now ask the students to incorporate into their work what I call the three pillars, namely: (1)thematic analysis of the films we watch for the course through one or two pre-established themes of the class; (2) film elements or, for the Italian cinema class, contextualization within the history of Italian cinema and further analysis through film elements; (3) and connections between what we see, read, and do in the classroom with the world outside. The last one is critical for the students, who must be able to see the links between their world and the world of the others, with the learning goal of fostering cultural appreciation and competencies.

To make this clearer, here is an example from the syllabus of my International Cinema class that I have been COILing with an institution abroad for the last couple of semesters and for which I have adopted the previously mentioned OER textbook. It is a set of guidelines for writing discussion board posts that offer deeper explanations and analyses according to the three pillars delineated above:

- Students are required to carry out the analysis of films through one or two themes of the class, which include: (1) food, (2) human communication (or lack thereof), (3) human understanding (or lack thereof), (4) gender roles, (5) identity, or (6) interrupted identity. This part of the discussion board is what I call thematic analysis, because students analyze a film through a pre-established lens (i.e., the themes).

- While analyzing films and supporting their points/theses through particular scenes (synopses of entire films should never be included), students are required to incorporate film elements (mise-en-scène, narrative, cinematography, editing, sound, acting, etc.) as studied in the assigned OER textbook using direct quotations (in quotation marks) or paraphrases with citations (example of style: Sharman, 2020, p. 124). This part of the discussion board is what I call film elements, because students identify some film elements as important parts of film construction.

- Finally, students are asked to explain how the films and their main points can be relevant to them and/or society. This part is what I call connections, because this part connects the class content (the films) with the world outside the classroom.

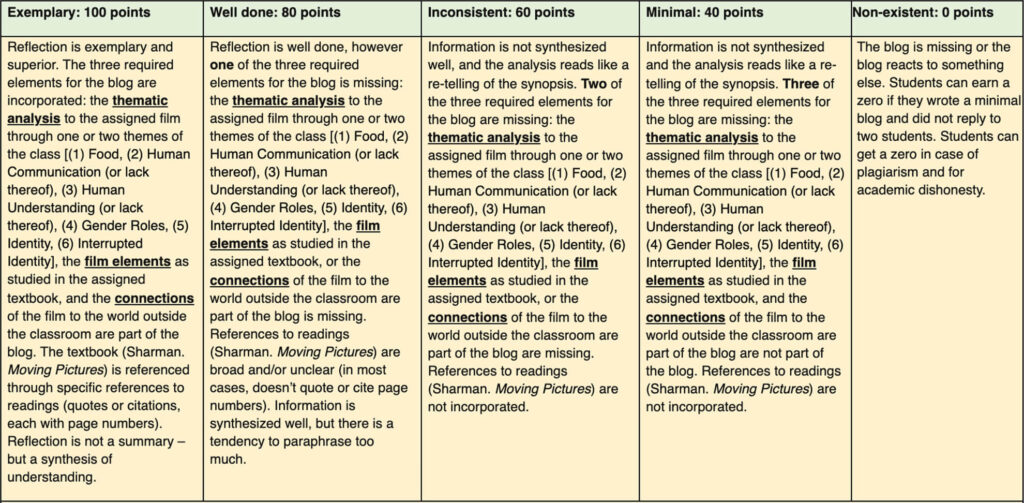

Now that you know more about the current structure of the discussion boards as I revised it to integrate the three pillars, you might be curious about the grading criteria. As is the case for most of my assignments, I grade the discussion boards using a rubric (in which initial student discussion posts are referred to as blog posts):

As for the results of my first semester (fall 2020) employing this new, more structured discussion board format, students were more engaged with each other and were able to make connections that were valuable and meaningful to their learning outcomes. While I can’t confirm if and what they will retain from my course in International Cinema after graduation, several students shared that the discussion boards structured by the three pillars also helped them to analyze the films they watched outside of class for entertainment, especially the first two pillars of thematic analysis and contextualization/film elements. Regarding the third pillar, students also shared that connecting the films to the world outside the classroom was a way for them to better understand their own world and the world of others as represented in international films, and a way to appreciate cultural diversity. Finally, one particular student stopped me after our last class of the semester (taught remotely, of course) and told me that this course had changed his life: the student shared that he had chosen the International Cinema course as an elective with the intention of studying business, but after having taken it, he decided to get an undergraduate degree in cinema. As you can imagine, this made my fall 2020 semester!

References

Ahlburg, D.A. (ed.). (2019). The Changing Face of Higher Education: Is There an International Crisis in the Humanities? Abingdon, Oxon, UK, and New York, NY: Routledge.

Bivens-Tatum, W. (2010, November 5). The ‘Crisis’ in the Humanities. Academic Librarian. Retrieved January 30, 2021, from blogs.princeton.edu/librarian/2010/11/the_crisis_in_the_humanities/

Brandl, K. (2008). Communicative Language Teaching in Action: Putting Principles to Work. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Prentice Hall.

De Santi, C. (2018a). Lezioni accademiche, lezioni pratiche: l’insegnamento della cultura italiana tra storia e gastronomia. Cultura e Comunicazione, VIII/12 (March), 12–17, 48.

De Santi, C. (2018b). (E-)Portfolios as a Final Project in Language Classes. Mosaic, 12(2), 179–186.

De Santi, C. (2018c). L’insegnamento della lingua e della cultura italiana attraverso la gastronomia: cuciniamole! TILCA, Teaching Italian Language and Culture Annual (Special Issue), 108–125. Retrieved January 30, 2021, from tilca.qc.cuny.edu/wp-content/uploads/2018/TILCA%202018%20Special%20Issue.pdf

De Santi, C. (2020a). Il mio 11 settembre nel marzo del 2020. Non quasi, ma tutto online ai tempi del coronavirus. Griselda Online: Il Portale di letteratura. Retrieved January 30, 2021, from https://site.unibo.it/griseldaonline/it/diario-quarantena/chiara-de-santi-mio-11-settembre-marzo-2020

De Santi, C. (2020b). Between Interdisciplinarity and Experiential Learning in Online and Hybrid Culture Courses. ILCC Challenges in the 21st Century Italian Courses, 1, 30–49. Retrieved January 30, 2021, from https://repository.library.georgetown.edu/handle/10822/1060512

Italian Food Culture in Practice (at Fredonia). (n.d.). Retrieved January 30, 2021, from https://italianfoodcultureblog.wordpress.com/

Larsen-Freeman, D., and Anderson, M. (2011). Techniques & Principles in Language Teaching (3rd ed.). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Plumb, J.H. (ed.). (1964). Crisis in the Humanities. Harmondsworth, UK: Penguin Books.

Schmidt, B. (2018a, July 27). Mea Culpa: There is a crisis in the Humanities. Sapping Attention. Retrieved January 30, 2021, from http://sappingattention.blogspot.com/2018/07/mea-culpa-there-is-crisis-in-humanities.html

Schmidt, B. (2018b, August 23). The Humanities Are in Crisis. The Atlantic. Retrieved January 30, 2021, from https://www.theatlantic.com/ideas/archive/2018/08/the-humanities-face-a-crisisof-confidence/567565/

Sharman, R. (2020). Moving Pictures: An Introduction to Cinema. University of Arkansas. OER Textbook. Retrieved January 30, 2021, from https://uark.pressbooks.pub/movingpictures/part/introduction/

“What Is COIL?” (n.d.). Intro 2 COIL. Retrieved January 30, 2021, from https://online.suny.edu/introtocoil/suny-coil-what-is/

Spring 2021: Curriculum Innovation for Transformative Learning