What Do Ads, the Economy, Films and Laws Have in Common? A Transdisciplinary Approach to Enhance the Teaching–Learning Experience

Published in:

November 22–23, 2019

University of Miami

Miami, Florida

Abstract

The United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) offer universities an innovative and inclusive way to communicate and demonstrate how they can contribute to global and local well-being. This paper presents the process, the conversations, and the results of an innovative new course. This process allowed four teachers to share their knowledge, passion, and creativity to create a course focused on active learning and project-based learning. The new course focuses on the United Nations’ SDGs, promotion of a better and more inclusive society, a transdisciplinary approach to the identification of problems and solutions, and co-teaching. The GRRASS model includes the following elements: Goals, Results, Responsibilities, Actions, Standards, and Schedule that promotes and facilitates the decision-making process and the planning of courses in the co-teaching modality. The sustained dialogues are presented as a continuous process that allows transdisciplinary collaborations in teaching.

Keywords: Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), innovation, co-teaching, transdisciplinary, sustained dialogues

Introduction

The United Nations declaration “Transforming our world: the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development” is one of the most ambitious and transcendental global agreements. The agenda, with the 17 Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), is a guide to address the most urgent global challenges: by 2030 to end poverty, promote economic prosperity, social inclusion, environmental sustainability, peace, and good governance for all (UNESCO, 2017). Universities can contribute to the implementation of the SDGs by providing innovative solutions, knowledge, and ideas in their curriculum. They must also commit to training current and future promoters and managers to implement the SDGs and develop leadership among sectors and social actors that guide the SDGs. The following is a summary of the process, conversations, and commitment of four professors who designed a relevant and impactful course for their students and whose focus was the SDGs. The outcome course: Trans-disciplinary experience: Innovation and development.

These four professors shared their knowledge, passion, and creativity to create a course that incorporated active learning and project-based learning to offer students and teachers an innovative and relevant learning experience. This course also proposes thematic discussions and the search for solutions from a transdisciplinary perspective. Specifically, the course was designed with the professors’ disciplines in mind: Social Communication (Advertising and Film), Economics and Law, although it can be adapted and taught by professors from other disciplines. This effort allowed the transformation of the learning experience considering the global challenges of the 21st century. Also, the process and dialogues of the teachers contributed to the analysis of the integration of content, significant teaching methodologies, and became a proposal for a transdisciplinary and team-teaching course.

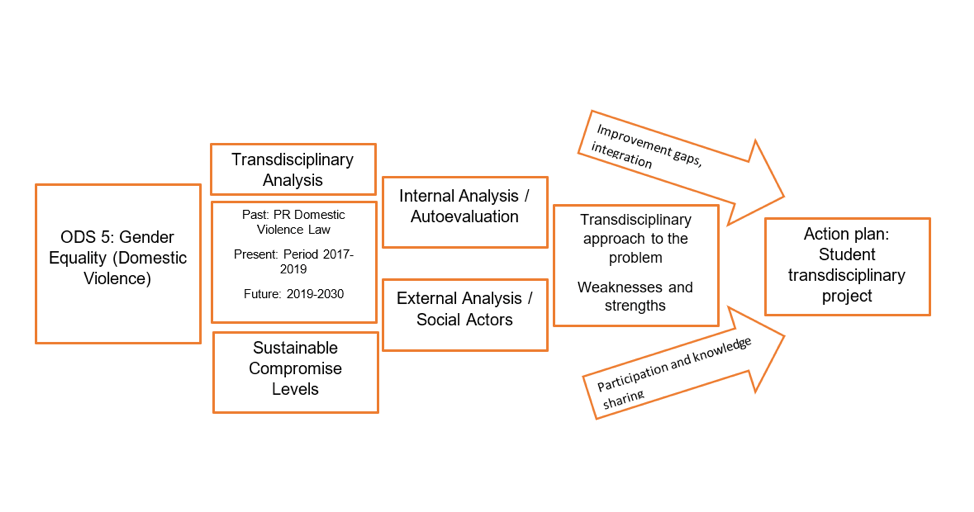

The following figure shows the 15-week course, taking as an example the fifth objective of SDGs, Gender Equality, and the problem of domestic violence, which was selected by the professors for the pilot course. Figure 1 reflects the decision-making process of teachers, transdisciplinary, and the co-teaching model selected by teachers.

Co-teaching

Co-teaching through disciplinary subjects and limits allows instructors to find new content knowledge, as well as new perspectives for themselves, and have the potential to enhance experiences for both students and professors. The team-teaching methodology can broaden the pedagogical skills of the instructors while providing opportunities to reflect deeply on teaching and professional practices. In doing so, it seeks to promote the development of higher-order critical thinking skills by students. Achieving these positive results, whether for students or instructors, however, is not guaranteed. Stakeholders’ gains depend on careful preparation and execution, along with institutional support. Without paying attention to these factors, courses taught as a team can create significant barriers for students and instructors. Beneficial results are subject to decision-making processes. According to the literature, this process has four dimensions of collaboration: planning, teaching, evaluation, and integration of content (Davis, 1995).

The first three dimensions focus on the participation and roles of faculty members, identifiable teaching assignments, teaching interactions, and who writes and qualifies class assignments. The content integration dimension is related to the unity and coherence of the course. The latter needs to identify in what ways and to what extent the multiple disciplinary perspectives are represented.

The following four dimensions of collaboration are relevant for multidisciplinary, interdisciplinary, and transdisciplinary courses. Three of these dimensions apply to any course taught in a team.

Planning: Do all team members participate in the planning, or do some team members play a more prominent role in course planning than others? How well have the course objectives been developed? Do the objectives reflect the opinions of all participants?

Teaching: Do all team members participate equally in the delivery of the course? Do teaching responsibilities fall into identifiable time segments, or do teachers intermingle their teaching day by day?

Tests and evaluation: Who writes and who qualifies exams and papers? Who takes over the process, and who decides when students question the process, including their grade? Who decides what mechanisms will be used to get feedback on the course, satisfaction levels, and concerns?

The fourth dimension is content integration, which is particularly applicable in multidisciplinary, interdisciplinary, and transdisciplinary situations. This dimension reflects questions such as: In what ways, and to what extent, the multiple disciplinary perspectives been represented? Are the different perspectives considered contradictory or complementary? Do different disciplines provide different lenses to see the same phenomena, or do disciplines examine different phenomena? Are the perspectives different, and are they related in some logical way, or have the perspectives been integrated to produce a new way of thinking? Is any unifying principle, theory, or set of questions used to provide unity and coherence to the course?

Co-teaching models

If the four dimensions presented above are considered as a continual potential for collaboration, it is possible to identify a series of co-teaching or team-teaching models. The most common co-teaching models are:

- Conference / Section or Conference / Laboratory: This model is widespread and divides the teaching between a senior instructor who works with all students (for example, at a conference) and graduate students that work with subsets of students in smaller conference/discussion/laboratory settings.

- Primary instructor: The primary instructor develops the lessons, course materials, and course policies, thus establishing the general course of the course. Guided by these materials, additional instructors teach the course in different sections. Students interact only with their section instructor.

- Coordinated Sections: The instructors collaborate in the design of the course (identifying common themes and tasks) but implement the course with their different groups of students and evaluate the work of their students. Students interact only with their section instructor. Periodic meetings of all instructors facilitate the necessary adjustments as the course develops.

- Sequential or rotational: The instructors establish in collaboration with the basic structure for the course and its students, but do not share the planning of the individual class sessions. Each instructor implements his or her part of the course for which he determines the material to be covered and the teaching modalities to be used. When questions arise, students are encouraged to communicate with the instructor responsible for the particular segment of the course involved. Each co-instructor is responsible for the tasks qualified in his part of the course, designing and qualifying those tasks.

- Specialty: The instructors collaboratively plan the course and individual class sessions but teach according to their area of expertise within or between class sessions. This may mean that the role of the instructor varies depending on the class segment or class session. The tasks are planned together, although the qualification can be divided to reflect areas of experience.

- Co-facilitation: The instructors plan in collaboration with all the elements of the course, from selecting readings and creating assignments to structuring individual class sessions that guide and facilitate together. Students can contact any instructor for office hours or clarifications. Instructors share grading responsibilities and coordinate on how to provide feedback and guidance on student work.

The teachers of this course decided to select the co-facilitation model as it is the most appropriate to obtain the desired results. It is understood as transdisciplinary to create a unity of intellectual frameworks beyond disciplinary perspectives. In order to achieve a problem analysis and approach to transdisciplinary solutions, the four professors must be involved in the design of the course, teaching, and evaluation. Besides, it was essential for professors to model transdisciplinary in the classroom to their students to encourage, among them, this way of analyzing and presenting solutions that bring the country closer to the fulfillment of the selected SDG.

The process: GRRASS

The process of planning and decision making for the creation of a co-teaching course require sustained dialogues among instructors. The dialogues also ensured and facilitated it to be a transdisciplinary experience for everyone involved. This dialogue process recognizes the existence of conflicts or differences between people and seeks to transform those relationships through phases that fit the needs and characteristics of each group or community. The continuous process, which is based on the transformative qualities of dialogue, allows interdisciplinary collaborations in teaching. At the end of the course designed, and after a reflection process, professors Ballester and Brugueras summarize the process and the dialogues by using the GRRASS model: Goals, Results, Responsibilities, Actions, Steps, and Schedule (Ballester-Panelli & Brugueras-Fabre, 2019).

- Goals: What is the intention or purpose of the conversations and the project? In other words, why have the dialogues?

- Results: What specific results should be achieved at the end of the conversations? At the end of the process or the course?

- Responsibilities: What roles or responsibilities must exist for conversations to run smoothly? For the project to be completed and succeed? What is expected of the participants?

- Actions: What actions and activities the group and individuals will perform, and in what order, to move towards the desired outcome?

- Standards (guides): What guides will be applied during the conversations? What are the agreed rules of the group? Consensus or majority? Online communication, face-to-face?

- Schedule: What is the expected time for conversations? For planning? For the project?

The GRRASS model is presented as a guide for other teachers when designing multidisciplinary, interdisciplinary, and transdisciplinary courses and adopting one of the co-teaching models. Besides, it can be incorporated into courses in which students are expected to analyze, make decisions, and present course projects through sustained dialogues.

Conclusion

The process, conversations, and results of the development of an innovative course, significant impact and relevance for the university, allowed four professors to share their knowledge, passion, and creativity. This process of designing the course was made possible because of the existence of natural groups. Natural groups (tribes) can be formed between people of similar interests, passion, and shared goals. The members of the tribe encourage and motivate each other. Their relationships imply high levels of commitment, innovation, creativity, and the search for a greater good. This is key to collaboration. (Logan, King, and Fischer-Wright, 2011).

The course is a means to contribute to the implementation of the SDGs and lead current and future promoters, and those responsible for implementing the SDGs. Students and professors have the valuable opportunity to provide innovative solutions, knowledge, and ideas that help achieve the United Nations’ SDGs and the development of a better and more inclusive society. The transdisciplinary approach to the identification of problems and solutions and co-teaching is presented as the appropriate way to approach the SDGs, their problems, and solutions. The GRRASS model (Goals, Results, Responsibilities, Actions, Standards, and Schedule) promotes and facilitates the decision-making process and the planning of courses in the co-teaching modality through dialogues. Sustained dialogues allow transdisciplinary collaborations in the teaching and design of projects that facilitate the implementation of the SDGs.

References

Ballester-Panelli, I., Brugueras-Fabre, A. (2019). What do Ads, the Economy, Films and Laws have in common? A transdisciplinary approach to enhance the teaching-learning experience. Presented at Faculty Resource Network 2019 National Symposium: Critical Conversations and the Academy, University of Miami, Miami, Florida, November 15-16, 2019.

Davis, J. R. (1995). Interdisciplinary courses and team teaching. Phoenix, AZ: American Council on Education and The Oryx Press.

UNESCO (2017). Education for sustainable development goals: Learning objectives. UNESCO, Paris. Retrieved from unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0024/002474/247444e.pdf

Logan, D., King, J. P., & Fischer-Wright, H. (2011). Tribal leadership: Leveraging natural groups to build a thriving organization. New York: Harper Business.

Morin, E. (1999). Seven complex lessons in education for the future. UNESCO, Paris. Retrieved from unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0011/001177/117740eo.pdf

Plank, K. (Ed.) (2011). Team teaching: Across the disciplines, across the academy. Sterling, VA: Stylus. SDSN General Assembly 2017 The role of Higher Education to foster sustainable development: Practices, tools, and solutions, Position paper.

Spring 2020: Critical Conversations and the Academy