Cultivating Global Competencies in a Diverse World: Pedagogical Strategies and Assessment of Student Learning in the Community College Classroom

Published in:

November 17–18, 2017

Dillard University

New Orleans, Louisiana

Abstract

This presentation reported on the implementation of pedagogical strategies for integrating global competencies into the Borough of Manhattan Community College curriculum and the classroom assessment of student learning. Participating faculty in the humanities described assignments targeting four global competencies adopted from the Michigan State University Liberal Learning and Global Competence Framework: cultural understanding, responsible global citizenship, effective intercultural communication, and integrated reasoning. A formative, continuous assessment approach was used in the classroom to inform the design and implementation of enhanced assignments. Formative assessments included reflective practices, self- and peer-evaluations, and rubrics to evaluate performance in, for example, capstone projects targeting a global competency.

Introduction

In 2010 the National Education Association (NEA) released a policy brief on the critical role of public education in promoting global competence as a 21st-century imperative (Van Roekel, 2010). The NEA asserted that the increasingly interconnected and interdependent global society required that American students develop habits of the mind that include tolerance, a commitment to cooperation, an appreciation of our common humanity, and a sense of responsibility. Aligned with the NEA approach, the Borough of Manhattan Community College (BMCC) of the City University of New York strategic plan, Bridge to the Future (2008), established globalization as one of four strategic pillars, based on the premise that a 21st-century education must provide community college students with an awareness and knowledge of diverse cultures and global issues, a set of skills that facilitate effective intercultural and interpersonal communication, and a commitment to be socially responsible citizens in a diverse and increasingly interconnected world. To that end, the strategic steering committee for BMCC’s globalization initiative developed a global competency initiative called Integrating Global Competencies Across the Curriculum, a professional development program to support faculty in the redesign of curricula to infuse global competencies into course offerings in the humanities (BMCC, 2008). The program was implemented with support from the National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH) Bridging Cultures Initiative (NEH, 2011).

In this program, participating faculty attended a series of seminars with invited scholars in global education, discussed challenging readings/issues in globalization, and shared pedagogical approaches to integrating global competencies in the curriculum. Faculty then enhanced three assignments to target specific global competencies and implemented the assignments the following semester. To inform the design of these assignments and to measure the effectiveness of the enhancement in the development of the targeted global competencies, individual faculty conducted ongoing formative assessments during the semester (Wiseman, 2016; 2017).

This presentation highlighted assignments created by participating faculty in speech and communication, economics, linguistics, and critical thinking. Presenters identified the global competency targeted in the design of an assignment, described the assignment and how it was enhanced to target different dimensions of the targeted competency, and explained their individual approaches to assessing the impact of the assignment on student learning.

Defining Global Competency

The definition of global competency has been debated over the years as the forces of globalization have increasingly impacted our lives. The definition of global competencies has in large part been the work of national organizations (Cummings, 2001), but with the increasing complexity of the global world, educational institutions have also developed models of global competency to ready graduates for career success. In 1996, twenty-three community college officials and representatives of government agencies met at a conference convened by the Stanley Foundation, which supports research pertaining to global education, and the American Council on International Intercultural Education (ACIIE, 1996). The conference, titled Educating for the Global Community: A Framework for Community Colleges, sought to define the term “globally competent learner.” Participants determined that a globally competent learner is one who is “able to understand the interconnectedness of peoples and systems, to have a general knowledge of history and world events, to accept and cope with the existence of different cultural values and attitudes and, indeed, to celebrate the richness and benefits of this diversity” (p. 4).

Targeted Global Competencies

A useful framework for operationalizing the construct of global competency was developed by Michigan State University (2010). The Liberal Learning and Global Competence Framework linked global competencies to define liberal learning goals and outcomes. The intention was to create a framework encompassing active engagement in learning in and outside the classroom so that, upon graduation, students would be able to demonstrate the knowledge, attitudes, and skills needed to be outstanding leaders and lifelong learners in the global village. Four global competencies from this framework were adapted for the BMCC initiative Integrating Global Competencies Across the Curriculum: cultural understanding, effective communication, responsible citizenship, and integrated reasoning. The underlying construct for each competency was defined with specific performance criteria.

Cultural Understanding

The BMCC graduate comprehends global and cultural diversity within historical, artistic, and societal contexts. This includes:

- Understanding the influence of history, economy, politics, geography, religion, gender, race, ethnicity, and other factors on his or her identities and the identities of others;

- Recognizing the similarities, differences, and dynamic relationships existing among people and cultures;

- Exploring explicit and implicit forms of power, privilege, inequality, and inequity;

- Engaging with, and being open to, people, ideas, and activities from other cultures as a means of personal and professional development.

Enhancement of an Assignment: Language and Culture (LIN100)

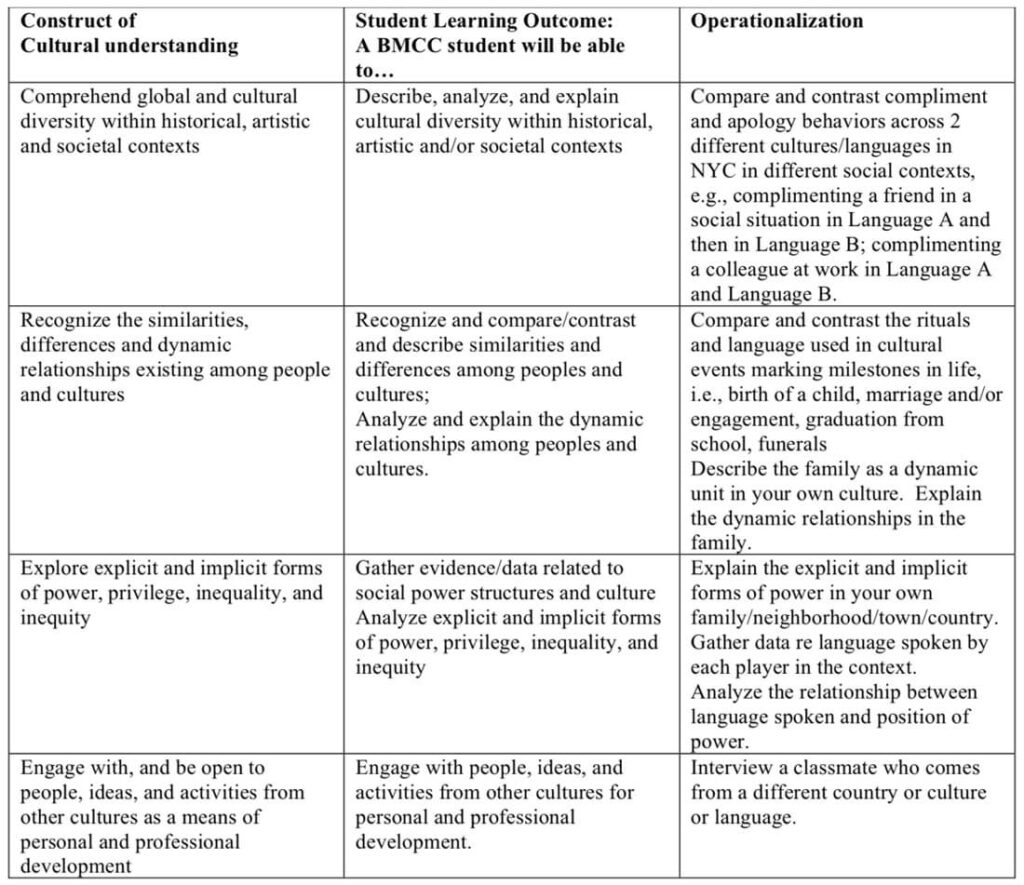

An assignment from the introductory linguistics course Language and Culture (LIN100) targeted cultural understanding. Cultural understanding was defined in the Liberal Learning and Global Competence Framework (MSU, 2011) as the understanding of global and cultural diversity within historical, artistic, and societal contexts. The professor first identified student learning outcomes that aligned with the underlying construct of cultural understanding as defined by the MSU framework and then operationalized that construct through the design of the assignment (see Table 1). For example, competency in cultural understanding could be demonstrated by explaining how culture or ethnicity shapes one’s identity or by comparing and contrasting differences in how language is used across cultures, such as in giving compliments or making apologies. Cultural understanding could also be developed through analyzing the relationship of language and power: for example, how military or economic power contributes to the development of a global language, or how speaking that language gives access to power. After articulating student learning outcomes, the professor developed an assignment to operationalize the construct.

A task-based assignment was created to explore the relationship of language and power through an analysis of the language varieties spoken by the characters in a film, and how the language of the characters reflected the power structures in the larger society as represented in the context of the film. Students were asked to watch a film of their choice but several films were suggested, including Precious, My Fair Lady, and Crash. They were asked to write a critical analysis of the social and political issues in the film, of the language varieties that were spoken in the film, and of how language reflected the social and political issues and power structure locally and more broadly in society. Students were instructed to write a reaction paper on the use of dialect or language variation in the film and not to simply summarize what happened in the film. Students were encouraged to search for a script of the movie online to help in the analysis of the language used. They were also asked to include in the discussion of language and power personal observations about dialects in our culture. They were invited to share personal experiences of reactions to their own dialect or language variety or with the “language of power.”

This task-based learning assignment targeted the development of cultural understanding and provided a framework for analysis and reflection on the relationship of language and power.

Classroom Assessments

According to Samuel Messick (1994), sometimes cited as the father of modern assessment, the design of an assessment instrument is determined by the purpose of the assessment. To assess the effectiveness of this initiative, it was thus necessary for faculty to consider the primary purpose of their individual assessments, and whether the enhancements in assignments targeting particular global competencies did indeed result in some measurable change in global competency. Both formative and summative assessments were used to measure change or transformation in global competencies of participating students. Participating faculty were encouraged to use formative assessments in their classes to inform ongoing instructional decisions or to determine whether instruction had been effective. As with any formative assessment practice, this involved setting goals or student learning outcomes aligned with the construct of the targeted competency (as explained above), engaging in frequent feedback with students, adjusting instructional practices in response to assessment data, and engaging students in the assessment process by providing individual instruction and opportunities for self-assessment. These formative assessments provided feedback to inform assignment revision and to provide feedback on student learning. The formative assessment for the LIN100 assignment was a reflective practice, asking students to reflect on the project before beginning the project, while doing the project, and after having finished the project:

BEFORE the project (5pts)

Please read the language observation project description. Post a thread in which you explain what you think the project is asking for, what you think you will do and why (i.e., the questions that you will ask and why you will ask those questions, based on what part of the readings), and what you think you will find when you analyze the dialect used in the literature excerpts, or consider the language used in a film that you watch, and how the use of language/dialects reflects existing political, cultural, economic or education power structures in society.

AS you collect the data and write it up (5 pts)

Reflect on what you are finding as you transcribe or analyze the language data. What are you looking for? What are you considering? What are your personal impressions/opinions/attitudes? Can you relate to the language of the speaker? Why or why not?

AFTER you have written up your 3rd language observation project (5 pts)

Reflect on this project. What were your expectations or assumptions before you started the project and how were they modified or confirmed by doing the project? What did you learn from the project?

The professor responded to the content of the student reflections. The feedback collected through the reflections informed the revision of the assignment.

Conclusion

The BMCC initiative Integrating Global Competencies into the Curriculum provided professional development for faculty across the humanities to foster the development of assignments targeting global competencies essential for college readiness and career success. Faculty enhanced course assignments to focus on issues related to globalization and developed assessments to inform teaching and learning and to measure changes in student self-perception of their global competencies. Feedback so far has been positive and it is hoped that the College will opt to continue this professional development initiative.

References

The American Council on International Intercultural Education Conference (1996, November). Educating for the Global Community, A Framework for Community Colleges. Paper presented at the Stanley Foundation and The American Council on International Intercultural Education Conference, Warrenton, VA.

Braskamp, L.A., Braskamp, D.C., & Engberg, M.E. (2012). Global perspective inventory (GPI): Its purpose, construction, potential uses and psychometric characteristics. Chicago, IL: Global Perspective Institute Inc.

BMCC. About BMCC. Retrieved from www.bmcc.cuny.edu

BMCC (2008). A bridge to the future: BMCC strategic plan 2008-2013.

Cummings, W. (2001). Current challenges of international education. Educational Resources Information Center, Office of Educational Research and Improvement. Washington, D.C.

Hunter, B., White, G.P., & Godbey, G. (2006). What does it mean to be globally competent? Journal of Studies in International Education 10(3), 267-285.

Messick, S. (1994). The interplay of evidence and consequences in the validation of performance assessment. Educational Researcher 23(2): 13-23.

Michigan State University Office of the Provost (2010, November). Liberal learning and global competence framework at MSU.

National Endowment for the Humanities. About the Bridging Cultures Initiative. Retrieved from www.neh.gov

Ramos, G., & Schleider, A. (2016). Global competencies for an inclusive world. Secretary General of the OECD.

Soland, J., Hamilton, L.S., & Stecher, B.M. (2013). Measuring 21st century competencies: Guidance for educators. A Global Cities Education Network Report. RAND Corporation/Asia Society.

Stevens, M., Bird, A., Mendenhall, M.E., & Oddou, G. (2014). Measuring global leader (GCI). Advances in global leadership 8 (pp. 115-154). Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

Van Roekel, N.P.D. (2010). Global Competence is a 21st Century Imperative. An NEA Policy Brief, PB28A. NEA Education Policy and Practice Department/Center for Great Public Schools.

Wiseman, C. (2017). Integrating global competencies into the curriculum. In FRN National Symposium Proceedings from Teaching a New Generation of Students.

Wiseman, C. (2016). Integrating global competencies in the curriculum. In Ramos, F. (Ed.), Proceedings from the II International Colloquium on Languages, Cultures, Identity, in School and Society (pp. 1-11).

Wiseman, C. (2014). Cultivating global competencies in the BMCC classroom: A BMCC strategic steering committee on globalization initiative. BMCC Faculty Focus. Retrieved from www.bmcc.cuny.edu

Spring 2018: Engaging With Diversity in the College Classroom