The Liberal Arts as a Practical Education: Helping Students Make Connections Between Liberal Arts Majors and Future Employment

Published in:

November 16–17, 2012

Dillard University and Xavier University of Louisiana

New Orleans, Louisiana

Abstract

This article focuses on two models of a liberal arts education in America–traditional and interdisciplinary–and discusses future employment for a graduate with a liberal arts degree presented by Pamela McKelvin-Jefferson from New York University (NYU) at the recent Faculty Resource Network (FRN) symposium on New Faces, New Expectations. Employers seek to hire well-rounded individuals with good communication skills, problem solving abilities, and achievement across a variety of general and specialized fields. This paper will assist faculty mentors and advisors in deciding whether their program is meeting the standards of the industry. If not, how does one go about instituting change within the structure of the department?

Introduction

What is a liberal arts education? The traditional American liberal arts education was modeled after an elite form of undergraduate education taken from the colleges of England’s Oxford and Cambridge Universities. In the past, only the children of wealthy families received a liberal arts education concerning the subjects and skills necessary to take an active role in civic life. Today the foundation of a liberal arts education reaches across many disciplines with an emphasis on interdisciplinary study and fields such as history, literature, philosophy, music, art, writing, and the sciences. It is viewed as a well-rounded education. According to Rosemary Keefe (2001), a liberal arts education leads to a longer and healthier intellectual life, helps develop analytical and research skills, fosters creativity, and develops oral and written communication skills, all of which make the student more open to cultural diversity. These are some of the conditions that foster student learning:

- Small institutional size;

- A strong faculty emphasis on teaching and student development;

- A student body that attends college full time and resides on campus;

- A common general education emphasis or shared intellectual experience in the curriculum; and

- Frequent interaction in and outside of the classroom between students and faculty and between students and their peers.

Do Differences in Liberal Arts Colleges Affect Student Outcome?

It is a fact that the more prestigious liberal arts colleges spend nearly five times more money than the less affluent liberal arts colleges. NYU’s Liberal Studies department is a good example of an administration and faculty placing a great deal of emphasis on curricular and co-curricular activities along with a highly structured “common core.” According to Alexander W. Astin (1999), it is a fact that private liberal arts colleges are in certain respects more diverse than any other type of higher-education institution. Therefore, these differences affect student outcomes in three ways: 1) educational; which can be measured in the student’s educational experience, what he or she learned, and how was the student changed; 2) existential; reflected in the quality of the educational experience, was it challenging and meaningful; and 3) fringe benefits which deals with the practical value of the education itself, such as social networking with alumni to further career goals and other advantages of being associated with a particular institution. However, there are differences in liberal arts colleges.

A national comprehensive survey completed by faculty members of 221 colleges and universities shows that highly selective/elite private liberal arts colleges, mostly independent, differ from Protestant, Roman Catholic and Historically Black liberal arts colleges by size, peer group, and faculty dynamics. According to Astin’s research, there are several factors involving faculty that affect an institution’s environment:

- interest in students’ academic issues;

- concern for students’ personal problems;

- commitment to the welfare of the institution;

- sensitivity to minority issues;

- accessibility;

- numerous opportunities for faculty-student interaction;

- students being treated like a number rather than a person; and

- placing a greater emphasis on teaching rather than research.

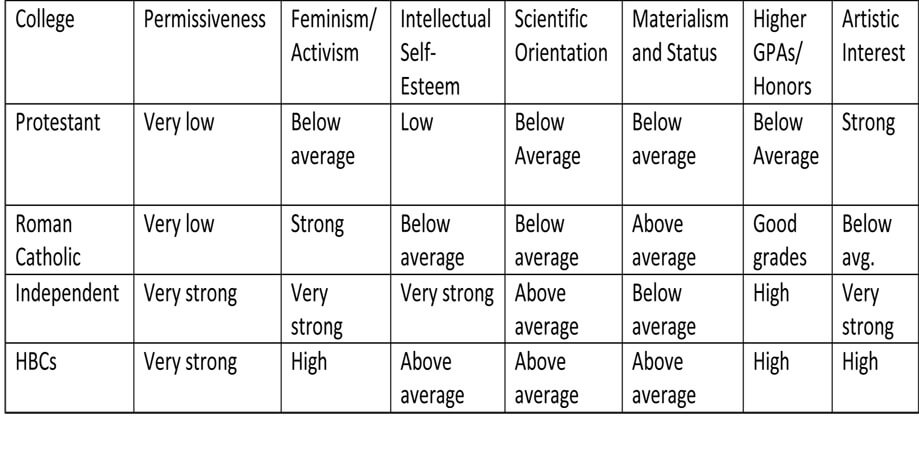

These unique effects as stated above can be explained by the climate created in the three major types of private liberal arts colleges plus HBCs shown in Table 1 below. Even though there are similarities in the groups, this is a snapshot of the individual who enrolls in those institutions rather than the long-term effects that liberal arts colleges can have on student development. What do we know about the quality of education received by the student in these institutions? The long-term evidence suggests that student outcomes can be directly linked to a student enrolling into graduate studies, winning a fellowship, and eventually earning a doctorate’s degree. The dilemma that faculty usually face is the emphasis put on teaching versus research. In an opinion poll of 212 baccalaureate-granting institutions across the country conducted by Astin and Chang, it was revealed that faculty members at highly selective liberal arts colleges achieve a better balance between research and student engagement. It was also found that environmental factors had a more positive outcome on the student by enhancing student involvement through educational practices such as frequent student-faculty/student-student interactions, generous expenditures on student services, clubs and other co-curricular activities, and a strong faculty emphasis on diversity. Note that highly selective liberal arts colleges are known for their best educational practices in higher education. This is not to say that the less selective colleges do not also employ these practices, just not on the same scale.

Table 1. Unique Effects of Various Types of Liberal Arts Colleges. Adapted from Astin (1999), How the Liberal Arts College Affects Students, pages 83-89.

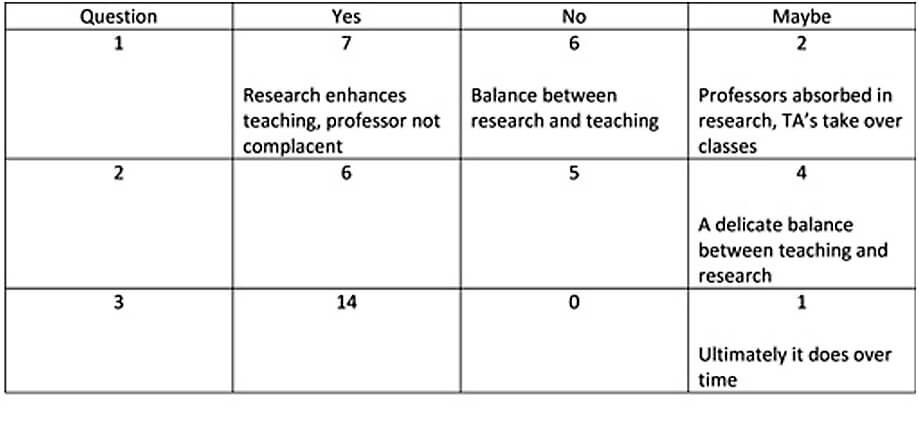

Astin and Chang’s poll measured two factors: student and research orientation defined as standard practice of a university or college. The findings show institutions that are strongly research oriented have weak student orientations and vice versa. Rarely will you find an institution strong in both areas. At the FRN Symposium, the author took a brief opinion poll of those attending the session. The fifteen professors present responded anonymously to the following questions: 1) Does a significant emphasis on research and scholarship necessarily come at the expense of student development? 2) Is it possible to emphasize the research function without sacrificing student development? 3) Can faculty research at liberal arts colleges actually be used to enhance the educational process? The result of the poll is shown in Table 2 below. Although we could not ascertain the strength of each responding professor’s college in research and student orientation, one thing is clear from their statements: professors who vigorously engage in research have less time for one-on-one student interaction. However, on a case by case basis, our poll revealed that it really depends on the professor. For reasons discussed above, highly selective liberal arts colleges have been able to reach a balance between research and teaching as stated in their research (Astin, 1999).

Looming Problems of Liberal Arts Education

Having described the benefits enjoyed by students at the highly selective institutions, one would think that these colleges would serve as a model. However, what seems to be happening on the undergraduate level is a watered down curriculum. This can be explained by the following changes made during a massive expansion within the system during the 1950s and 60s:

- Increase in department size with an emphasis on research and graduate education;

- Faculty does little or no academic advising; and

- Undergraduate instruction is done by graduate students, part-time or adjunct instructors.

Maybe the solution now lies in our government officials deciding to invest in American’s educational system. New innovative programs will put us back into the driver’s seat. We know that graduates of highly selective and elite colleges are found disproportionately in leadership positions in politics, culture and the economy, but what about the rest of the population? We need well educated people in all sectors of society for this country to be truly successful. The changing face in education is already reflected in various colleges around America, particularly our community colleges.

Who Are the College Students of the 21st Century?

In 1998 Ernest Pascarella and Patrick Terenzini did a study focusing on the changes in college students in the 21st century. What they found was that there was a dramatic shift beginning in the 1980’s where the growth of Asian, Hispanic, African-American, and Native-American undergraduates jumped by 61% and by 1994 this same population accounted for 25.7% of the national undergraduates in urban institutions ranging in age from 25 to 30 years old. A recent report from the National Center for Education Statistic (1996) showed that 46% of all college students between the ages of 18-24 have full-time jobs and work at least 20 hours per week.

Due to this culturally and economically diverse student body, which ranges in both age and life experience, the traditional liberal arts education has been modified for the new global era. Faculty members are re-designing curricula and strategies to help diverse student populations to develop strong analytical and communication skills, providing them with real world experiences, and integrative education which have multiple structured opportunities to make connections across disciplines and fields. At NYU, we offer career development opportunities at the career services office (Wasserman Center) to help students begin to market themselves and their liberal arts degrees. The center also provides one-on-one counseling, mock interviews, workshops, on-line resources, custom job searches, job fairs, and on-campus interviews with companies seeking students for employment as interns or permanent staff after graduation.

Multicultural Education Programs

NYU has a whole host of programs designed to provide the student with a variety of experiences to become a well-rounded person. This fact is reflected in opportunities such as the Intergroup Dialogue Program, which is a nationally recognized one-credit course that brings together small groups of students from different backgrounds to share their experiences and gain new knowledge related to diversity and social justice. Our service learning program is a particular form of experiential education combining community service with academic instruction which focuses on critical, reflective thinking, and civic responsibilities. Students can also participate in the Alternative Breaks Program, which teaches them about political and social community dynamics in a collaborative setting during winter/spring break or weekends while working on issues such as, literacy, poverty, homelessness, racism, or disaster relief.

Other programs across NYU that aide in meeting the Formative Themes (Schneider, 2004) in the reinvention of a liberal arts education as mapped out by the Association of American Colleges and Universities are: 1) CAS Speaking Freely program, which is a non-credited language course; 2) NYU’s Civic Team, which provides the student with an opportunity to volunteer or intern at one of nearly 40 not for profit or government agencies in NYC; 3) Jumpstart NYU is also a national non-profit early education organization which inspires children to learn, adults to teach, families to interact, and communities working together, 4) NYU Project Outreach, which helps new undergrads and transfer students to connect with NYC’s diverse community service organizations through a four day emerging leadership program and orientation; and lastly, 5) The School of Continuing and Professional Studies (SCPS) is ideal for students who never received a degree and are returning to school after some time off. The average age of a SCPS student is 27 years old. They can receive credit for real life working experience through the Experiential Learning Credit program. SCPS offers professional development courses; a variety of certificates in fields such as real estate, publishing, marketing, web development, as well as an associate, bachelor, or master’s degree.

Conclusion

It is obvious that better prepared students tend to interact more frequently with faculty. We see these educational practices being carried out most often in the selective liberal arts colleges. However, research shows that students at nonselective liberal arts and public colleges would also benefit from frequent contact with professors but the evidence “suggests that faculty who teach such students frequently assume that they need a more traditional, didactic kind of pedagogy (Tsui, 2002). A successful liberal arts education develops the capacity for innovation and for judgment (Roth, 2008). We, as professors charged with the duty of educating today’s youth, must not forget that everyone is important and that we must meet the need where they stand. Employers are searching for skilled individuals on all levels of the economic stratus; students with strong analytical and communications skills. As educators, we too must prepare ourselves for the “new face” in our classroom and meet the “new expectations” of the changing student population!

References

Astin, A. W. (1999). How the liberal arts college affects students. Daedalus, 128(1, Distinctively American: The Residential Liberal Arts Colleges), 77-100.

Harris, R. (2010, October 15). On the Purpose of a Liberal Arts Education. Retrieved from http://www.virtualsalt.com/libarted.htm

Jones, R. T. (2005). Liberal Education for the Business Expectations. Liberal Education, 91(2), 32-37.

Keefe, R. (2001, February 15). What is the Value of Studying the Liberal Arts? Retrieved from http://www.uwsuper.edu/advise/studentinfo/liberalarts.cfm

Pascarella, E., & Terenzini, P. (1998). Studying College Students in the 21st Century: Meeting New Challenges. The Review of Higher Education, 21(2), 151-165.

Roth, Michael, (2008, January 1). What’s a Liberal Arts Education Good For? Huffington Post. Retrieved from http://www.huffingtonpost.com/michael-roth/whats-a-liberal-arts-educ_b_147584.html.

Schneider, C. G. (2005). Practicing Liberal Education, Formative Themes in the Reinvention of Liberal Learning. Liberal Education, 90(2),6-11.

Tsui, L. (2002). Fostering Critical Thinking Through Effective Pedagogy: Evidence from Four Institutional Cases. The Journal of Higher Education, 73(6), 740-763.

Spring 2013: New Faces, New Expectations