Cross-Disciplinary Digital Literacy in the Age of Apps and Mobile Devices

Published in:

November 18–19, 2011

University of Puerto Rico, Rio Piedras and University of the Sacred Heart

San Juan, Puerto Rico

This document represents the unified interest and collective knowledge and experience of three faculty members from multiple courses in three disciplines (art, communication arts, and sociology).

Internet Digital Literacy

In the digital landscape, “reading” is multi-sensory and often non-linear, and “writing” requires the ability to express ideas in multiple formats including text, images, video, blogging, or tweeting. Digital tools afford opportunities for collaborative reading and writing (particularly in wikis, virtual spaces like Second Life, video conferencing like Skype, and cloud-based tools (i.e. software or storage services that are provided over a network connection like Google Docs) in ways that pen and paper cannot accommodate. The ability to self publish instantaneously (particularly in cloud-based apps) without the vetting process of traditional print publication leads to a large spectrum of resources, information, and materials all of varying quality. This abundance of digital platforms implies that digital literacy includes the ability to evaluate digital media in addition to consuming and producing it.

Students already use some of these platforms and technologies in the work they do, regardless of whether the student is fluent in the platform or method, or the instructors have addressed how best to use tools or to evaluate resources. In addition to traditional library resources (the library website, librarians, computers, and printed materials), students seek out research materials using their own laptops and smartphones using a variety of source finders: search engines (primarily Google and Bing); blogs; Google Scholar; Amazon and Google Books; Facebook; Twitter; Wikipedia; and Ask a Librarian. Any one of these methods could lead a student to fantastic resources, but they also can lead to dated, falsified, biased, or plagiarized information.

The Mobile Student

Traditional-aged college students are a highly mobile population and are likely to remain mobile beyond graduation. Based on Blackboard submission data and emails to instructors, we can see that they complete course work at all hours and in all sorts of contexts—coffee shops and eateries, in the hallway, the library, at home, in public transportation, at work, and outside—all indicating a desire and expectation of flexibility. Laptop ownership among 18-29 year olds is at 70%. Adoption rates of smart phones are particularly high in this group, 52% compared to the entire American adult population (35%). A quarter of all smart phone owners use their phones as their primary connection to the internet and rates are higher among younger owners (Smith, 2011).

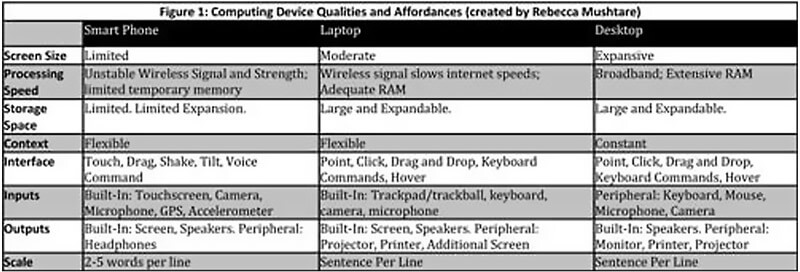

When we think about the way college students access information and tools to complete their coursework, we must consider mobility and mobile access. Working on and with a mobile device requires a user to depend on cloud services (Dropbox is an option that we use) to save, move, and print media which results in a work-flow and experience different from a standard desktop computer (see Figure 1 for a comparison). Most mobile users rely on their tablets or phones for internet access and research, digital reading, taking photos, and videos. They then transition to a laptop or desktop when media needs extensive editing before publishing.

Unfortunately, online resources are not necessarily designed to accommodate all platforms. A student who attempts to interact with assigned online material may not have the experience intended by the instructor. For example, a student might not be able to access all of the content on their mobile device (often because the site requires a Flash Plug-in for dynamic content), or the formatting requires excessive zooming and scrolling (reading a twenty-page PDF on a smart phone demonstrates this well), or the formatting causes overlapping content, or the site may refer the user to an app that may limit the scope of the available content. Checking a resource on multiple devices in advance of students can assist the instructor in providing a meaningful experience for all students.

Using a cloud service like Dropbox for student assignments removes extra steps for the mobile student (or faculty member) by providing instant access to documents and media in a shared folder available from any device. Combined with other tools like the iPad app, “Good Reader,” a paper can be graded and returned electronically as a PDF. E-textbooks and iPad textbooks (that also come in a print form), like those from Inkling, offer a textbook experience that is rich in media and in a form students are comfortable and familiar with.

Using a consumer-level free platform like a wiki (we have used Google Sites) or a blog (we have used WordPress) as a course management system extends the classroom into a public space, provides access from any device with internet access, and facilitates dialogue about the role these platforms play (and can play) in larger political, economic, and social conversations. Unlike a traditional CMS, wikis and blogs are used in a variety of sectors in the workforce to initiate information exchange, collaboration and knowledge building (for example, this document was written using such a platform). Both wikis and blogs also encourage the development of an intellectual community within and across courses as students collaboratively construct knowledge.

Mobile technologies can also be used to conduct field research, particularly at the advanced level. Many students have great research tools in their mobile devices, like high quality cameras, audio recorders, location awareness (GPS Tagging) and many blogging and wiki-services provide easy ways to publish this content from the mobile device. For example, in a Sociology of Art class, students visually documented a museum exhibition of African art, for the purpose of critique. Once uploaded to the Wiki, the class was able to engage in a broad discussion and analysis of the discourses that inform curatorial practices. While this engaged the students’ personal mobile technologies, apps designed to conduct social research like Revelation and EthOS, may be more useful in future endeavors.

Inherently cross-disciplinary assignments require students to conduct thorough research. As students use the media sharing, hyperlinking, and embedding features of these platforms, interesting questions are raised about intellectual integrity, attribution, copyright, plagiarism, validity of sources, privacy and identity that are important to address from many disciplinary lenses as we help transition students to digital citizenship.

Classroom Dynamics

Use of Apple’s iPad as a teaching tool in combination with platforms like blogs and wikis has shifted the teacher-student relationship in the classroom. The iPad allows a faculty member to be free of a “frozen” style of lecturing—sitting behind an over-sized computer monitor while projecting images onto an even larger screen—to walking around the classroom with relevant media to share with individual students. The iPad has the capacity to bring back an intimacy of teaching and learning that has diminished with the increase of “bigger and better” technology in our computer labs and “smart” classrooms. The iPad permits a focus on individuals and small groups rather than forcing a consistent pacing or experience for all students with a singular projection. Students find the workload easier to manage when there are ready references, physically close at hand, and there is the ability to discuss their work one-on-one during class.

A shift from “analog pedagogy” to “digital pedagogy” means dismantling the professor-student hierarchy of the classroom. Using digital skills in the classroom requires each constituent to invest a level of trust and a willingness to experiment with a variety of technologies and in a variety of capacities. In this model, the role of the “expert” fluidly shifts between all participants (students and faculty). Similarly, the ability to share resources and expertise outside of the classroom can be facilitated through the class wiki or blog. For example, a student assignment to analyze articles from the New York Times using course concepts in an “analog” pedagogy requires the student to write a paper and attach a clipping to which a faculty member reads and responds to. The same assignment in a wiki platform enables students to link directly to the article, integrate related media, and use the collective forum for a student-student conversation in addition to a student-teacher conversation. This transition is best captured in Dr. O’Connor’s observations of her sociology classroom, “Though we discuss the concept of ‘power’ endlessly in sociology and I consider myself to be conscious of power relations, the shift to a digital pedagogy practically critiqued a non-collaborative aspect of my classrooms to which I had been blind. Integrating the sociological analysis of society with the democratic nature of Wiki writing brought to life the critique of the key sociological concepts of power, authority, and hierarchy.” In this sense, the shift to a digital format effects the relations of the classroom—empowering students means transforming the power relations of the classroom.

Moving from Consumers to Producers

In keeping with our college’s mission to develop students’ awareness of social issues and to develop their skills to improve society, we focus on digital media as a tool to empower the student and his or her ability to understand society and effect social change. By providing content, requiring research, challenging students’ visual and design skills, introducing students to new expressive forms and demonstrating the connectedness of varying disciplines, we enable students to empower themselves as active producers rather than passive consumers.

Different disciplines afford different opportunities for “production.” As more people are able to express their ideas to a large audience with the increasing ubiquity of digital technologies, it has become increasingly critical to train students to responsibly conceptualize, create and distribute innovative, politically and socially engaged thoughts using contemporary media technologies. Given the expanding arenas of nonfiction media (activist events, news, documentary, gaming, commentary, criticism, and forms not yet defined), Professor Burns has encouraged her art students to create work that elevates public awareness and enlivens the possibility of public interaction. Providing visual design problems while introducing students to new visual and design ideas demonstrates the connectedness of other art forms and strengthens visual and design skills. Special emphasis is given to problems in context and visual analysis, as a preliminary step is required. Students are encouraged to use any tool at hand for experimentation and/or to test their ideas. As we transition from analog to digital, assignments change from designing for print (posters, brochures, announcement cards) to designing for screen viewing (tablet, smart phone, gaming device). The coursework allows students to benefit from analytical and experimental approaches to solving visual design problems, and from the interplay between those approaches. Recent visual design assignments have addressed the Mirabal sisters, Wangari Maathai, Marcelo Lucero, autism, HIV transmission prevention and environmental issues like global warming, greenhouse gases, and wind power. Similarly, in her courses, Prof. Mushtare has facilitated collaborations between community organizations and students to create websites, web resources and digital games that have recently addressed homelessness prevention, hoarding, the sexualization of girls, and dialogue about Islam. In each of these projects, students have refined their digital skills both by creating media and by teaching community partners how to use the tools. These projects and methodologies not only “empower” students to be responsible to their education, but also fostered a sense of shared commitment to the classroom and the community.

Towards Digital Citizenship

Active citizenship in the United States increasingly requires the use of information technology and the skills, knowledge, and access to interact through digital tools. Citizenship increasingly means creating blogs, using social networks and other means of digital communication to organize, share, protest and participate in larger political, economic and social discussion. To participate actively requires an understanding of the scale of and the very public nature of writing (text, video, image, sound, etc.) online.

It requires the understanding of privacy, contract and copyright laws, the ability to protect one’s own contributions, and the willingness to acknowledge and properly attribute the work of others. An individual’s digital identity begins the first time anyone signs up for an email address, posts pictures online, uses e-commerce, and/or participates in any electronic function and evolves into a non-linear web of references and points of participation. Lack of digital participation can be a serious drawback, since many elementary procedures such as tax report filing, employment and school applications, political campaigning, governmental documents, news reporting, and research studies have migrated to the internet. Non-digital citizens will not be able to retrieve this information and this may lead to social isolation or economic stagnation. The digital divide is the gap between active digital citizenship (which goes beyond access to technology) and non-digital citizens. What can you do in your classroom to narrow the gap?

References

Smith, A. (2011). Smartphone adoption and usage. Pew Internet & Life Project. Retrieved from http://www.pewinternet.org/Reports/2011/Smartphones.aspx

Spring 2012: Emerging Pedagogies for the New Millennium