Academic Advisement to Help Students Engage with the Community: Faculty Perspectives on the Process

Published in:

November 19–20, 2010

Howard University

Washington, D.C.

To provide students at a large urban community college with the academic advisement essential for academic success, the Borough of Manhattan Community College (BMCC), City University of New York (CUNY), instituted an extensive advisement program that included a team of faculty, staff, and administrators trained to provide academic support. While the advisement program was founded on current advisement models that incorporate mentoring and establish advisement communities, this model was unique in that faculty advisors were instrumental in the design and implementation of this program. This study explored faculty perspectives on academic advising, their roles as faculty advisors, and the student-advisor relationship.

BMCC hosts a diverse student population of over 24,000 students speaking more than 100 languages. Many are first-generation students and many are over 21 years of age. The college offers 23 majors and students who graduate are awarded the Associate in Arts (A.A.), the Associate in Science (A.S.) or the Associate in Applied Science (A.A.S.) degree. The largest population of students is in the liberal arts. These students traditionally have had the highest attrition rates as well.

A Middle States evaluation in 2003 asserted that the single most pervasive and critical problem the college faced was “the issue of academic advisement and the limited support services afforded the college’s liberal arts students and their faculty” (Title V Project Abstract 30). To address the issue, BMCC obtained a $2.4 million Title V grant to improve the academic advisement process for the liberal arts population. The main components of the program included 1) the adoption of a developmental advisement model; 2) the recruitment and training of faculty advisors; 3) the hiring of educational planners on staff at the Academic Advisement and Transfer Center (AATC) to act as liaison between students and faculty; 4) the recruitment of faculty to mentor other faculty; and 5) the development of an electronic system to record the outcome of advisement sessions and faculty mentors. The resulting comprehensive advisement program is outlined in the graph below.

An underlying central premise of this program was that training faculty to be academic advisors would ultimately improve student success in the liberal arts, helping students become more dynamic decision-makers in their educational programs and in their life choices. Selke and Wong (1993) maintained that faculty members make ideal advisors because “no person has greater potential to affect a student’s…[academic] experience [than the professor]” (p. 22). Indeed, establishing a personal relationship with the faculty has been recognized as one factor in promoting retention (Lotkowski et al., 2004; Tinto, 2006).

Faculty members also make good advisors because they are adept at creating an environment that facilitates both learning and student development in ways consistent with the goals of developmental advising as it is typically understood. As Lowenstein (2005) pointed out, key components to academic excellence overlap with those of successful advising. These components include strategies for getting students to reach the upper levels of Bloom’s taxonomy, such as integrating and organizing knowledge, planning, assessing, choosing, evaluating, prioritizing, and predicting. Translated into an advising session, the key components for advisors for the BMCC Advisement Program thus became mentoring students to help them in the following: goal setting (the exploration of life and vocational goals); decision making (decisions regarding program and course choice as well as scheduling of courses); developing a sense of accountability (student and advisor-student); building strategies for academic success; building relationship (faculty-advisee); and encouraging self-regulation and self-determination.

While prior research suggests that faculty advisors play an important role in academic advising, the data regarding faculty conceptualization of their roles and responsibilities as advisors are limited. Johnson and Zlotnik (2005) found that only 7.5% of 636 ads for professorial positions in the Monitor on Psychology mentioned advising. Harrison (2009) observed that student advising is given “short shrift” compared to teaching, research and service, and “remains largely bureaucratic” (p. 229). As O’Banion (1972/2009) noted, an academic advising model runs the chance of being a “perfunctory activity” that becomes “grossly ineffective” for most faculty advisors if faculty are not considerably committed to advising (pp. 87-88). If faculty advisors are to be successfully utilized in an academic advising model, their experience and input must be recognized and integrated in its design and articulation. Soliciting faculty feedback, and implementing faculty recommendations and suggestions in the design of the advising program model can translate into considerable faculty commitment. Moreover, examining and documenting faculty perspectives on their experience as faculty academic advisors are some of the objectives of this study.

To this end, we solicited feedback from participating faculty members regarding the advising program and how they conceptualized their roles as advisors and mentors. The faculty responses gathered in this study provided much-needed insight into how faculty viewed the academic advising process, their roles as academic advisors, and their relationships with their advisees. Faculty response also supported the assumption that a community of faculty, staff, and students is critical in sustaining a program that engages students and supports faculty commitment.

To gather data on the program, we distributed an online twenty-item survey to all 107 participating faculty advisors across the ten departments in liberal arts. The survey elicited faculty feedback on the components of the newly established advising program and the guidance they provided advisees, the knowledge and guidance provided in the training of faculty advisors, the usefulness of the advising materials developed, and the extent to which the establish advising community supported the advising relationship. Out of the 107 faculty advisors for liberal arts majors, a total of fifty-three faculty, representing all ten departments, initiated a response to the survey with a total of forty-five (84.9%) completing the survey.

Faculty provided a description of a typical advising session with advisees. The data suggested that the BMCC faculty advisors provided knowledge and guidance to advisees that would help these students make the types of decisions suggested in the theoretical models by O’Banion (1972/2009) and Lowenstein (2005). Faculty responses suggested that faculty were indeed trained to follow the developmental advisement model outlined in the BMCC Academic Advisement program: to allow students to make their own choices, establish long- and short-term goals, and in this way, to work with students in problem-solving and decision making (see Table 2). Faculty reports of academic advising sessions confirmed that they were implementing a development advisement model that took the whole student into consideration.

In a nutshell, a primary goal of the BMCC Advisement program was to train faculty in an advisement model meant to improve student success in the liberal arts, making students more dynamic decision makers in their educational programs and in their life choices. Respondents were asked to explain in their words the goals of developmental advisement as outlined in this model, and for the most part, their responses were congruent with the stated goals of the BMCC Title V advisement program. Their responses also reflected a shared sense of purpose to establish a long-term advising relationship with students based on “strong and consistent mentoring.” As reported by Wiseman and Messitt (2010), the following excerpts illustrate prevailing views of participating faculty regarding the goals of advisement program:

- “To provide students with consistent and reliable advising that helps give them a sense of connection to the college and a stronger sense of their own goals and the ways they can meet them.”

- “To assist faculty in becoming better advisors and to assist students in their academic and career choices through effective advisement.”

- “[It] makes the community smaller. Among faculty, [it] increases familiarity with different departments and resources at the college and also gives greater feeling of satisfaction in working with one student over the course of their college career rather than just once and at random during the registration period.”

- “It has been the first step in putting ‘community’ in the community college. It not only brings students and professors together but also professors together.”

Underscoring the positive impact of the advising community on students, a faculty advisor concluded:

- “It has been very positive and the word is getting around, at least in my experience, talking to students and those who are participating. I have spoken to various students, who are not in my cohort, and they are happy… to have someone to talk to and call that [they] have some kind of relationship with.”

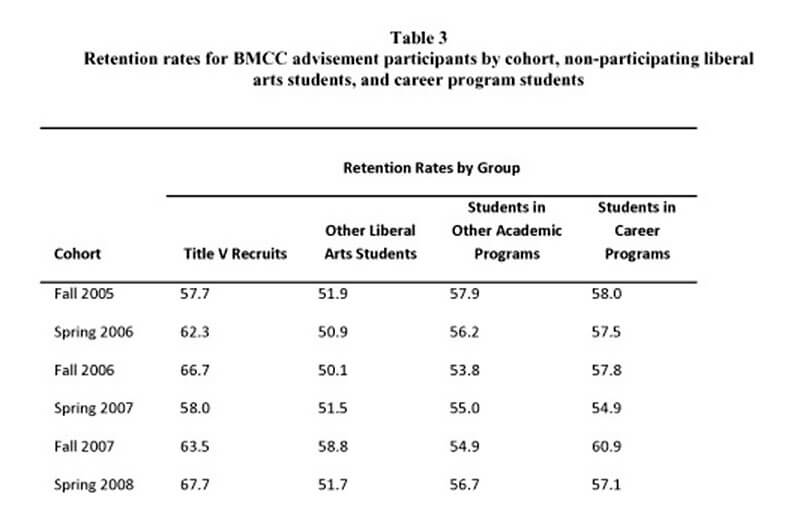

As a follow-up, we examined retention rates for students enrolled in the BMCC Title V Academic Advisement Program. Students participating in the advisement program achieved an overall higher retention rate among the various cohorts than other students in liberal arts, academic, and non-select career programs. As reported in Table 3, from fall 2005 through spring 2008, freshman-to-sophomore retention rates for liberal arts students participating in the program were higher than retention rates for non-participating liberal arts students, as well as students in other academic programs. While increases in retention rates cannot be directly attributed to participation in the advisement program, these results provided positive feedback to the faculty and staff.

Conclusion

Feedback from faculty advisors regarding their experience in the BMCC Advisement Program provided a rich description of a number of vital components of academic advising at the college. The results of the survey suggested that this initiative contributed to the development of a faculty-training program, which in turn generated the enhancement of support services to sustain effective advising and a community of shared purpose in advising. Faculty feedback further suggested that the advising program fulfilled the planners’ goal of providing knowledge and guidance to both students and faculty members alike.

This study provided an important piece to the puzzle of effective academic advising–the perspective of committed and engaged faculty advisors who are invested in the academic success of their students. Faculty responses demonstrated sensitivity to and understanding of academic, professional, and personal choices facing students. This suggests that faculty can be key players in a college’s success in providing guidance and support in student’s academic and career choices, thus effectively extending their roles beyond teaching, research, and committee work.

References

Harrison, E. (2009). Faculty Perceptions of Academic Advising: ‘I don’t get no respect.’ Nursing Education, 30(4): 229-233.

Johnson, W. B., and Zlotnik, S. (2005). The frequency of advising and mentoring as salient work roles in academic job advertisements. Mentoring & Tutoring: Partnership in Learning, 13(1): 95-107.

Lotkowski, V. A., Robbins, S. B., & Noeth, R. J. (2004). The role of academic and non-academic in improving college retention. Retrieved from http://qed.ncat.edu/beams/act-retention-study.pdf

Lowenstein, M. (2005). If advising is teaching, what do advisors teach? (2009) NACADA Journal, 29(1): 123-131.

O’Banion, T. (1972). An academic advising model. Reprinted (2009) NACADA Journal, 29(1): 83-89.

Selke, M. J. and Wong, T. D. (1993). The mentoring-empowered model: professional role functions in graduate student advisement. NACADA Journal, 13(2), 21-26.

Tinto, V. (2006). Taking student retention seriously. Retrieved from http://www.mcli.dist.maricopa.edu/fsd/c2006/docs/takingretentionseriously.pdf

Wiseman, C & Messitt, H. (2010). Identifying components of a successful faculty-advisor program. NACADA Journal, 30(2), 35-52.

Spring 2011: Engaging Students in the Community and the World