BOLD in Detroit: A Campus–Community Partnership

Published in:

November 20–21, 2015

New York University

Washington, D.C.

Introduction

Marygrove College, founded in 1905 and sponsored by the Sisters Servants of the Immaculate Heart of Mary, has a long tradition of excellence in education, social and environmental justice, and community engagement. Taking advantage of its location in the heart of a large urban setting, Marygrove seeks to influence and be influenced by not only its students but also by its neighbors in the city of Detroit. The three Cs of Competency, Compassion and Commitment complement our mission statement and are best realized when they are nurtured on the campus and applied in the work of students, faculty, and staff beyond the gates of the institution.

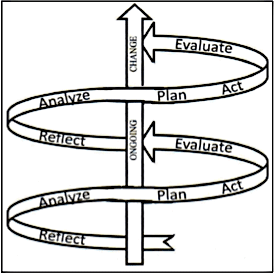

Participatory Action Research (PAR) is a “framework for creating knowledge that is rooted in the belief that those most impacted by research should take the lead in framing the questions, design, methods, analysis and determining what products and actions might be the most useful in effecting change” (Torre, 2009). In contrast to traditional research, not only does PAR require the community to define the issues, but it also requires collective action, informed by the research. The philosophy of Participatory Action Research (PAR) is consistent with the mission of Marygrove College, which sees a liberal arts education as engaging in interactive dialogue with others, both inside and outside the academy.

In Summer 2012, as part of the Marygrove College Building Our Leadership in Detroit (BOLD) Kellogg Foundation grant, we formed a PAR team of faculty and staff. Our goal was to help infuse PAR into Marygrove’s Urban Leadership curriculum and co-curriculum. To this end, we set out to create a PAR resource packet, build neighborhood relationships to understand and address community concerns, and infuse PAR methods into several courses.

Process

During our first year, we met weekly during the summer, sharing books, articles, websites, and other resources on the Participatory Action Research (PAR) approach to working with communities. As we discussed what we were learning, we were building our own team, learning each otherís strengths and weaknesses, and developing a tentative timeline for research and action. Our primary goal that year was to compile PAR resources, including a PowerPoint slide show, handouts, illustrated examples of PAR projects around the globe, and an annotated bibliography (see end of this paper). We developed a check list and community feedback tool to assess whether class projects are truly “participatory.” The team made formal and informal presentations to faculty groups and developed a PAR Blackboard site. We also revised course syllabi in the areas of social work, social justice, the first-year liberal arts seminar, and the humanities.

During the first and second years of the project, to develop relationships in our neighborhood and understand its concerns, PAR team members visited neighborhood block club meetings, met with police officers of the 12th Precinct, invited community people to PAR team meetings, participated in monthly “Co-Creating Community” sessions, and collaborated on a Community Resource Fair. We piloted a survey of community residents at six campus and community events to get a sense of community concerns. Data analyses revealed that the three highest-priority concerns were: blight, safety/crime, and youth engagement.

We initially revised several syllabi to include PAR values and then infused PAR values and practices into a 300-level interdisciplinary Social Research course (cross-listed with social work, criminal justice, sociology, and political science), so that our students—and the neighborhood—would actually experience PAR. This presented challenges given that we also had to meet the goals of the research course.

The Social Research course had initially included traditional lectures and exercises on research methods, as well as a hands-on experience developing and conducting an on-campus survey of students. The new PAR-infused version of the course gave birth to more interactive class sessions, and the first Marygrove Neighborhood Survey, which was developed and conducted by the students in collaboration with our PAR team and several community members. During that first semester, students carried out literature searches related to the three major community concerns (blight, crime/safety, and youth engagement), developed hypotheses, and drafted three survey questionnaires—one for each primary community concern. Initial drafts were shared with PAR team and community members, who provided extensive critique, until questionnaires were finalized. Then research teams of students, faculty, and staff members used the questionnaires for a door-to-door survey in the Marygrove neighborhood. Teams were transported by a campus security officer in a well-marked college van, while two faculty also patrolled in their cars. These arrangements assured both students and our neighbors of their safety, as neighbors were initially wary of strangers knocking on their doors, and not all students were comfortable with our Detroit neighborhood.

That first semester the survey questions focused primarily on gaining more understanding of the community’s concerns, as well as gauging respondents’ interest in getting involved to address those concerns. Students used SPSS to analyze the data. Key findings included:

- The majority of respondents agreed that blight is a problem.

- About half reported witnessing drug activity.

- About one-third reported being a victim of burglary and/or robbery.

- 68% of respondents were interested in helping with blight (e.g., cleaning up lots, boarding up houses).

A key component of PAR is collective action informed and led by those most affected by the issue. Hence, after the first year Neighborhood Survey, we planned a Neighborhood Action Meeting to identify specific action projects of interest to our neighbors and neighborhood residents who would act as liaisons with our PAR team.

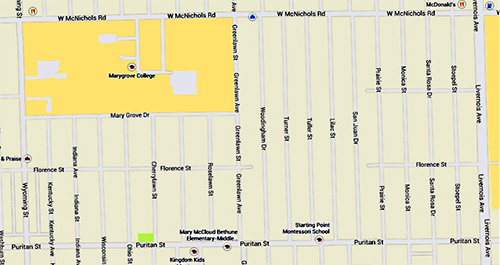

To invite neighbors to the meeting, the PAR team, supported by students and alumni, leafleted the entire Marygrove neighborhood (see map below) and visited local organizations and businesses. About 40 neighbors attended, sitting at tables according to residential blocks, and each table was facilitated by two Marygrove representatives (PAR team members and Social Work/Social Justice students). After introductions, each table identified a community liaison and specific desired projects. Marygrove facilitators were charged with collaborating with community liaisons to shepherd projects through completion.

At the Neighborhood Action Meeting, eight priority projects were identified. During our second and third years, the PAR team began working with assigned community liaisons to implement some of the identified actions:

- Removal of dumped tires: We contacted a local church that recycles and re-purposes tires; they collected tires from three sites in the neighborhood; these sites have remained free of dumped tires since then.

- Cleanup of a seven-lot area at San Juan Street: Two evenings each week during summer 2014, PAR members, neighbors, and students worked to clean up overgrown lots on San Juan Street. By Fall Term 2015, Marygrove Campus Ministry, headed by a PAR member, sponsored a Halloween “Trunk-or-Treat” for over 100 neighborhood children on those cleared lots.

- Cleanup of a small vacant lot on Wisconsin Street: We visited this lot with neighbors, but plans to proceed were stymied by bank ownership of the vacant lot.

- Promotion of facilities and youth programs at Maggie Lee’s Community Center: The PAR team contributed to a Back-to-School Book Drive at Maggie Lee’s Community Center, which is located in the neighborhood.

- Conducting a workshop on fund-raising and 501(c)3 status, especially for members of the Marygrove Community Association (MCA) and Maggie Lee’s Community Center: An MA Social Justice student facilitated a workshop on Board Member Certification and Grassroots Funding. The 85 neighbors and students who attended received a Certificate of Nonprofit Board Leadership from the Johnson Center for Philanthropy at Grand Valley State University, a collaborator in the workshop.

- Provision of student volunteers to work with the MCA on organization and surveys: We have so far been unable to provide regular volunteer assistance to the organization.

- Creation of an online resource list (e.g., Facebook page, web page): Our PAR team began a list of businesses, churches, programs, and other institutions serving this neighborhood; a team member has volunteered to create websites on free platforms for the Marygrove Community Association (MCA) and Maggie Lee’s Center, and another has offered to create and maintain Facebook pages.

- Re-opening Marygrove campus gates along Marygrove Street and offering Marygrove library cards to neighborhood youth and leaders: We sent a memorandum to senior college administrators reporting neighbors’ desires for re-opening south campus and library access; in 2015, the College began opening south gates for special on-campus events open to the public.

Lessons Learned

- The PAR process is messy in academia, but so worth the effort. It is not easy, during the course of a semester, to carry out a PAR neighborhood survey, from start to finish, that is meaningful to neighbors as well as students. Supporting students through all the steps of the research process—including designing the questionnaire, conducting the door-to-door data collection, analyzing the data, and writing their research papers—requires planning, a great deal of outside classroom work, flexibility, and a good sense of humor. We have learned, for example, that questionnaires need to be limited to four pages, that many of our neighbors will not answer their doors before 11:00 on a Saturday morning, and that we need a “pick-up” option for those who cannot complete the survey on the spot. However, student evaluations and anecdotal information tell us that students feel the neighborhood survey is the best part of the course, and that the hands-on approach deepens their understanding and learning of both social research and PAR.

- Participatory Action Research has much to offer with respect to student learning. With PAR experience, students’ perspectives of social issues begin to change from focusing on individual responsibility or “blaming the victim” to asking, “What resources are missing in the community?” They shift from simple observations, such as “There’s a lot of drug activity,” to systemic questions concerning, in this case, the causes of drug use and sales in the neighborhood. In addition, students learn the value of mutual respect and the give-and-take of relationship-building. In the early stages of hypothesis and questionnaire development, students sometimes assume they can ask the neighborhood residents any kind of questions they want. Collaborating with neighbors around questionnaire development reminds students that trust is an important component in creating openness, and that being a “researcher” does not afford anyone license to be intrusive or rude.

- Strong neighborhood relations are a win/win for everyone. Our relationship-building and collaborative actions with neighbors have created a new synergy both on campus and in the neighborhood. For example, during the seven-lot San Juan Street cleanup, businesses donated equipment and supplies to support the endeavor. Recently a block club sign for the newly invigorated San Juan Block Club was posted near these lots, and a survey is underway asking neighbors about repurposing the area. Not one tire has reappeared in the neighborhood. Because neighbors have appeared at Marygrove events, there is increased networking and sharing of resources (e.g., a clothing drive for the neighborhood women’s shelter). And the “Trunk or Treat” event at the cleared lot is now becoming an annual event.

Future Actions and Conclusion

Although the three-year Kellogg grant ended after the fall term of 2014, our team has chosen to continue our work embedding PAR principles into our urban leadership curriculum, co-curriculum, and neighborhood actions. In winter 2016, we will again guide Social Research students in carrying out a Marygrove Neighborhood Survey in collaboration with the community. We also hope to interview approximately ten “key” neighborhood residents, who want to share more in-depth information about neighborhood strengths, concerns, and actions. We are learning NVivo so that we can better analyze qualitative data. In summer 2016, we will host another Neighborhood Action Meeting and conduct another Neighborhood Workshop. In addition, we are dreaming of “green mapping” the neighborhood—documenting our community resources, such as neighborhood businesses, churches, programs, institutions, community/recreational facilities, water sources, gardens, and open spaces. We also want to institutionalize a neighborhood database to track community changes.

We continue to solidify relationships with neighbors, local community organizations, and businesses. Community liaisons and other neighbors have begun to call us with questions, concerns, and invitations to their events and meetings. We are pleased to put into action, along with our neighbors, our Marygrove College values of Competence, Compassion, and Commitment.

References

Participatory Action Research: Basic Theory and Perspective

Campbell, J. (2011, January 4). 23. Introduction to methods of qualitative research participatory action research [Video file]. Retrieved from http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=8VSlDI0d7rA

Videos #23-33 in the series (10 minutes each) explain PAR’s four tenets, based on McIntyre (2008) and Cresswell (2006): collective commitment to engage an issue, reflection, mutually beneficial action, and alliances between researchers and participants. A pdf outline is at: http://nova.academia.edu/jasonjcampbell/Teaching/21593/Methods_of_Qualitative_Rese arch_and_Inquiry

James, E. A. (2008, June 3). Participatory action research + complexity [Video file]. Retrieved from http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=s-SAJPF5xiA

James briefly explains how PAR enables groups to address complex distributed problems, PAR as a strategic planning tool, and four key steps: research and evaluate issues; plan and implement actions on issues; measure results; and reflect on process and results. PAR is distinct from other approaches, and is informal and collaborative.

Lewin, K. (1946). Action research and minority problems. Journal of Social Issues, 2(4), 34-46.

In this brief article, Kurt Lewin, founder of action research in the United States, described action research as a cooperative effort that “proceeds in a spiral of steps, each of which is composed of a circle of planning, action, and fact-finding about the result of the action”(p. 38). The article describes a successful workshop for community workers in Connecticut.

McIntyre, A. (2007). Particpatory action research: Qualitive research methods series 52. Los Angeles: Sage.

A brief outline of PAR history and tenets. Two case studies exemplify three key aspects: developing participation, creating action, and gathering, analyzing and disseminating information. Reflection and collaboration are needed for “co-developing research programs with people rather than for people.”

McTaggert, R. (1989, September 3-9). 16 tenets of participatory action research. Available from The Caledonia Centre: http://www.caledonia.org.uk/par.htm

This important reflection on and distillation of the praxis of PAR lists key tenets of classic PAR approaches and provides links to McTaggert’s publications.

Torre, M. E. & Ayala, J. (2009). Envisioning participatory action research entremundos. Feminism & Psychology, 19(3): 387-93.

Torre, M. E., Fine, M., Stoudt, B. G., & Fox, M. (2012). Critical participatory action research as public science. In H. Cooper & P. Camic (Eds.), APA handbook of research methods in psychology, vol. 2, research design: Quantitative, qualitative, neuropsychological, and biological. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

This lengthy scholarly article is worthwhile for its historical coverage of Participant Action Research (PAR), and for an excellent analysis of a project done with urban teen males. The authors link specific project information to theory and values.

Examples of Participatory Action Research Projects

Cahill, C., Rios-Moore, I., & Threats, T. (2008). Different eyes/open eyes: Community-based participatory action research. In J. Cammarota and M. Fine (Eds.), Revolutionizing Education (pp. 89-124). New York, NY: Routledge.

A PAR project with young “womyn” from New York’s Lower East Side, who call themselves the “Fed-Up Honeys,” noted effects of urban stereotypes on young women. Interviews, surveys, mapping, and archival research confirmed that institutions used stereotypes to justify “fixing” youth deemed lazy, stupid, promiscuous, etc., rather than seeing youth as responding to a disinvested community. As action, “stereotype stickers” were placed in public spaces. The authors reflect that the project transformed their vision.

De Heer, H., Moya, E.M., & Lacson R. (2008). Voices and images: Tuberculosis photovoice in a binational setting. Cases in Public Health Communication & Marketing, 2, 55-86. Available from www.casesjournal.org/volume2

Describes how participants were empowered through using photography. This project increased TB awareness, cross-border collaboration and treatment compliance in El Paso/Ciudad Juarez. TB patients showed reduced shame and increased adherence to treatment, created photo exhibits, and influenced policy makers to address TB levels.

Foster-Fishman, P., et al. (2010). Youth ReACT for social change: A method for youth participatory action research. American Journal of Community Psychology, 46(1-2), 67-83.

This PAR project used several methods for local knowledge production and creating critical consciousness by engaging middle-school youth in all phases of the project: problem identification, data analysis, and feedback.

Greenwood, D., Whyte, W., & Harkavy, I. (1993). Participatory action research as a process and as a goal. Human Relations, 46, 175-189.

PAR is an “emergent” process and a powerful tool for problem-solving in complex challenges. Commitment to local knowledge and linking understanding to action are key. Three case studies detail the process, featuring the Fagor Cooperative Group of Mondragon, Spain; Xerox Corporation; and Philadelphia Public Schools and the University of Pennsylvania.

McIntyre, A. (2000). Constructing meaning about violence, school and community: Participatory action research with urban youth. The Urban Review, 32(2), 123-153.

McIntyre notes her students focused on “fixing” youth, not seeking wider contexts. Using PAR methods, the author worked with urban youth to explore how they “made meaning of their community” to address concerns. Violence was a major theme and so became the project focus. Collages, storytelling, and photography revealed that youth inherit unjust structures, and teachers can assist youth to articulate experiences and seek solutions.

Weis, L., & Fine, M. (2004). Working Methods: Research and Social Justice. New York, NY: Routledge.

Authors exemplify theories and methods used to interrogate structural systems of social injustice by PAR projects with women in prisons and students in urban high schools. They analyze dominance in societal structures, critique the master narrative, and look at counter-hegemonic viewpoints. PAR methods are detailed, as well as ethics and challenges of PAR and traditional research methods.

Social Philosophy Informing Perspectives of Participatory Action Research

Freire, Paulo. (2000). Pedagogy of the oppressed. London: Continuum Press. (Original work published in 1968)

A prolific writer, Freire was also a lawyer, philosopher, and educator. Freire helped sugarcane workers develop the literacy then required to vote, and was a lifelong advocate of adult literacy. His work, based on Marx and Fanon and akin to liberation theology, founded the critical pedagogy movement and has informed the work of Ngugi, Biko, Illich, Valdez, the World Social Forum, The Earth Charter, the eco-consciousness movement, and Theatre of the Oppressed.

Hooks, Bell. (1994). Teaching to transgress: Education as the practice of freedom. New York: Routledge.

Hooks provides educational critique and pedagogical strategies for engaging students to become enlightened witnesses and active citizens.

Illich, Ivan. (1971). Deschooling society. London: Marion Boyars Publishers.

Illich explains the critical difference between schooling and education, and how to educate for citizenship.

Trouillot, Michel-Rolph. (1995). Silencing the Past: Power and the production of history. Boston: Beacon Press.

Historian Trouillot illustrates how to unearth alternate voices silenced by the official histories of dominant elites, with examples from Haiti.

Spring 2016: Advancing Social Justice from Classroom to Community