HBCUs Punching Above Their Weight: Tougaloo College’s Re-Envisioning of the General Education Curriculum

Published in:

November 22–23, 2019

University of Miami

Miami, Florida

The ever-changing landscape of higher education demands that institutions—at all levels— engage in rethinking their approach to the classroom learning experience. This new approach entails utilizing teaching and learning methods that better equip students for the 21st century workplace. A number of studies have indicated that employers have experienced difficulties in finding employees with the skills necessary to complete the tasks of their positions— recognizing the skills mismatch – the gap between individual job skills and the demands of the job market (Capelli, 2012; Snyder, 2019; Craig, 2019). Many employers have also noted similar trends among recent graduates (Ejiwale, 2014).

Changing Labor Market and Skills Mismatch

There is a strong force driving the need for higher education institutions to re-envision their approach to learning which demands that these institutions be engaged in providing students with the opportunity to become exposed to and develop career-readiness skills. This trend is being driven by the view of college as a product in which students seek to purchase for a future benefit— a career. Conceptualizing higher education in such a way facilitates the desire for students to look at their educational experience through a rational-economic model of investments (time and labor) and returns (career prospects and future wages). In the same sense, employers hold to this same rational-economic model by holding institutions of higher education accountable for exposing and developing the desired soft skills necessary to complete job duties.

Numerous studies have pointed out that employers have noted that recent graduates are underprepared for the labor market and lack the necessary soft skills to assume the roles of their jobs (Strauss, 2016; The Bureau of National Affairs, 2018; Wood, 2018). This points to a lack of preparation during their college years and higher educational institutions’ lack of focus on cultivating the skills necessary for graduates’ competitiveness in the labor market. Of the soft skills, these employers have continually noted a lack of skills development in communication, teamwork, and leadership (U.S. Chamber of Commerce Foundation, 2018). These are soft skills that employers view as the building blocks of a carrying out the tasks of the workplace and for facilitating productivity of workers. When employees present without these skills, employers are faced with either investing money to train their workers or spend more money on talent search committees and hiring (Feffer, 2016).

This entails a proactive approach which recognizes our higher education institutional role in equipping students to leave their college experience as career-ready professionals (Repko, 2009). Studies of recent graduates note that students believe they embody the skills that employers believe they lack (Strauss, 2016; NACE, 2019). It can be assumed that this skills-mismatch and the perception of recent graduates have been facilitated by advances in technology that have shifted how we communicate and interact. The increasing use of technology by the millennial generation has helped to facilitate changes in the way people communicate. Students have begun to develop alternative communications styles that are not beneficial to workplace operations (Strauss 2016). This, as employers see it, presents difficulty for millennials in the workplace because there are generational differences in the work patterns that are not always beneficial to productivity in the workplace (i.e., our current workplaces include four different generations: Baby Boomers, Generational X, Generation Y, and Millennials).

Interdisciplinary Teaching and the 21st Century Workplace

Significant changes have occurred in higher education over the past 30 years as expectations of career-readiness for graduates have evolved. Interdisciplinary teaching has been used to address these changes in learning. Klein (1990) defines interdisciplinary teaching as the synthesis of two or more disciplines, establishing a new level of discourse and integration of knowledge. It is a process for achieving an integrative synthesis that often begins with a problem, question, or issue. Interdisciplinary pedagogies in higher education have proliferated as brain research has reinforced active and experiential learning as paramount to student learning. Moreover, this pedagogical approach engages students’ collaborative, cooperative, and team- based learning (Mitcham, 2010). The focus of interdisciplinary teaching in higher education creates the environment where students are able to develop cognitive abilities which contribute to significant learning over the duration of their learning journey (Field et al., 1994; Lattuca, 2004; Repko, 2009).

Higher educational institutions use of interdisciplinary teaching helps to facilitate cognitive development in students that goes beyond the classroom and furthers career-ready skills development, as students become introspective. Further, interdisciplinary teaching helps students develop their brain-based skills and mental processes that are needed to carry out tasks. Repko (2009) identifies three cognitive attributes of interdisciplinary teaching that facilitates students’ ability to learn: acquire perspective, develop structural knowledge, and integrate ideas and concepts. First, acquire perspective – students are able to develop a capacity to understand multiple viewpoints on a topic by considering various fields of knowledge in the evaluation process. This process allows students to develop an appreciation of the different disciplines and their discipline specific rules on how to approach viable evidence. Second, develop structural knowledge – students are able to engage and cultivate their cognitive skills by using declarative (factual knowledge) and procedural knowledge (process knowledge) to consider various domains of information to solve complex problems. This facilitates the opportunity for students to enhance their knowledge formation capacity and engage with complex conversations. The last attribute, integrate ideas and concepts – students are able to integrate conflicting insights from alternative disciplines. In all, interdisciplinary teaching promotes significant learning by impacting students with a range of skills and insights which promote student engagement in the learning experience and helps to reinforce and facilitate the development of the employer desired career- readiness skills.

21st Century Student Learning: Bringing It All Together

Utilizing the interdisciplinary teaching approach within the institutional context allowed for developing and implementing a number of initiatives which have been beneficial to student learning. These include the re-design of the general education curriculum (C.O.R.E.), the development of an e-Learning and service learning component, and the creation of certificate programs to complement degree requirements for all students. Each of these types of programs allowed for greater flexibility in teaching and a greater impact on students’ cognitive development as they engaged the learning experience.

C.O.R.E./Interdisciplinary Instruction

Curriculum Outcomes Redesigned for Engagement (C.O.R.E.) was developed to empower innovative teaching and foster autonomous student learning through student engagement and creativity. While C.O.R.E. brings focus to the design of the general education curriculum, C.O.R.E. goals, values, and outcomes are germane for each student’s matriculation. In essence, CORE is an analysis of the cognitive, ethical, and spiritual needs of today’s learners.

C.O.R.E. is a framework for the intentional design of a learning system focused on the needs of today’s learners. This framework emanates from a common set of student learning outcomes, focused on the development of student skills necessary for success in rigorous discipline study. The Tougaloo College student learning outcomes include: critical thinking, effective communication, cultural awareness, and independent learning skills (information literacy and self- efficacy/critical analysis). The intentional design of curriculum, methodology, delivery, and assessment brings new focus to the development of a connected learning culture dedicated to the empowerment of innovative teaching while fostering autonomous learning through student engagement and creativity. Cognizant of the changing demands of learning in this century, the Tougaloo College student learning outcomes unify the curriculum to focus on student skills.

e-Learning and Service Learning

Some of the greatest benefits of e-learning are convenience, flexibility, aligned to the 21st century student, digital record keeping, and can serve multiple learning styles. Also, students can earn academic credit hours towards a degree while working full-time. Regardless of whether students are traditional or non-traditional, they have the freedom to manage and organize their profession and education without the stress of being tied down to a predetermined class schedule (Community College of Aurora, 2020). There is no pressure to keep up with their classmates in a face-to-face classroom environment. Through self-discipline, students have the liberty of being in control of their own progress. Online learning allows students to take courses in the comfort of their homes (Dumbauld, 2017).

Service-learning combines learning goals and community service to increase student growth and provide a benefit to the community. Service-learning normally is integrated into a course or series of courses through the incorporation of a project that has active learning and community action goals. Projects are designed in conjunction with higher education faculty or staff and community collaborators. This allows students the opportunity to apply course content to community-based activities (Center for Teaching, 2020). Goals achieved from service learning include but not limited to guidance and hands-on experiences; enhancing critical thinking and problem-solving skills; connecting with professionals and community members; and deeper involvement in intellectual growth, leadership development, and personal and social growth.

Certificate Creation

Certificate programs enroll traditional and non-traditional students, as well as adult learners. Programs are normally utilized for professional development, career advancement, re- tooling, or personal interest (Suny Empire State College, 2019). Certificate programs can also meet the emerging needs for educational programs currently offered at an institution of higher learning. Certificate programs may be offered at the graduate and undergraduate level for both credit and non-academic credit (Academic Leadership Council, 2006). At Tougaloo College and partnering institutions (Oakwood University and Talladega College), our goal is to support the existing academic credit programs and utilize as many academic courses as possible that already exist. To make this process successful, we first collaborated with our partnering institutions. This allowed us to assess the student market or need inside and outside the state of Mississippi. Next, the population was identified and the evaluation of course delivery options. After building a team on Tougaloo’s campus, pre-existing degree programs and courses were reviewed and modified to meet student and workforce development needs. Most importantly, all certificate courses and programs were aligned with degree granting programs upon offering.

All faculty teaching in certificate programs were trained on how to use the institution’s online platform, as well as learning the differences and needs of non-traditional students through a series of approved modules. This is done through online and face-to-face professional development sessions. Faculty must be comfortable with offering courses online and be able to navigate the online portal to communicate with e-learning students both traditional and non- traditional.

Forward Thinking, Linking, and Workforce Development

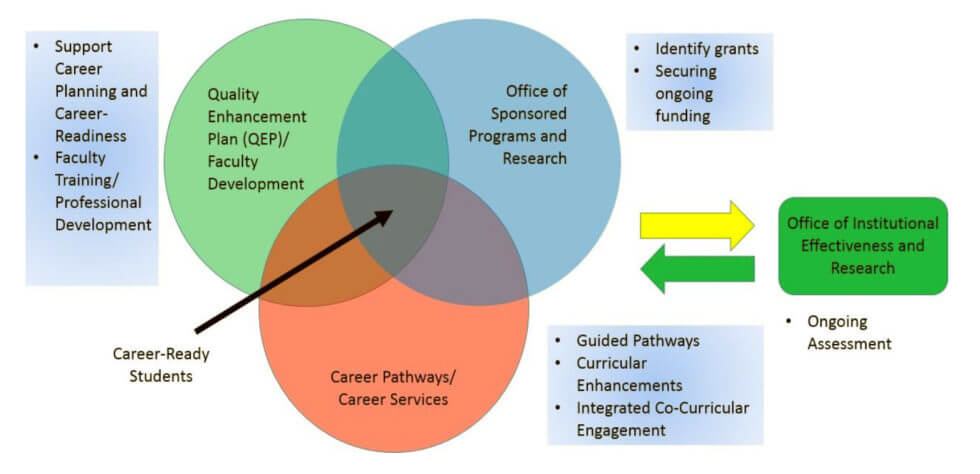

With the development of the Career Pathways Initiative on Tougaloo’s campus, we utilized external and internal partnerships, which assisted with the development and implementation of infusing the curriculum with interdisciplinary teaching with a career-readiness skills development focus. These included external and internal partners (See Figure 1 for a visual representation of internal partners).

The external partners included: 1) The United Negro College Fund (UNCF) Career Pathways Initiative, funded by Lilly Endowment, which is a $50 million investment over a seven- year period, that helps four-year HBCUs and PBIs strengthen institutional career placement outcomes with the goal of increasing the number of graduates who immediately transition to meaningful jobs in their chosen fields. 2) INROADS – whose mission is to develop and place talented minority youth in business and industry and prepare them for corporate and community leadership. There are three keys to success for INROADS students: Selection, Education & Training, and Performance. For over four decades, INROADS has helped businesses gain greater access to diverse talent through continuous leadership development of outstanding ethnically diverse students and placement of those students in internships at many of North America’s top corporations, firms and organizations. 3) ConneXions — the operations technology, developed by Tougaloo College, that improves delivery, efficiency, and effectiveness of career preparation to students, enhance their connections to career information, employers, alumni mentors, and others.

The ConneXions portal is multifaceted with three main areas: public portal, employer partners and alumni portal, and a job seeker/student portal. 4) National Association of Colleges & Employers (NACE) is the leading source of information on the employment of the college educated, and forecasts hiring and trends in the job market; tracks starting salaries, recruiting and hiring practices, and student attitudes and outcomes; and identifies best practices and benchmarks. NACE provides its members with high-quality resources and research; networking and professional development opportunities; and standards, ethics, advocacy, and guidance on key issues.

Figure 1 illustrates the one example of the many internal partnerships that were forged to carry out this type of programming. The internal partners included: 1) Office of Sponsored Programs and Research (assists in identify additional grants for sustainability); 2) Quality Enhancement Plan (QEP)/Faculty Development (supports career planning and career-readiness and faculty training/professional development); and 3) Office of Institutional Effectiveness and Research (provides ongoing assessment of all the components of Career Pathways).

Recommendations

This educational endeavor required exhaustive bureaucratic negotiation because of the nature of modifying the general education curriculum to align with educating 21st century students. Therefore, we present four recommendations that should be considered in light of our efforts. First, higher educational institutions should revisit their institution’s approach to the general education curriculum in order to question its continued relevance in preparing students with the needed career-readiness skills. Second, identify pathways that link curricular and co-curricular programing to ensure its relevance toward career-ready exposure. Third, create partnerships between faculty and employers, which will assist in the facilitation of improved classroom instruction and focuses on bridging theory to practice. Finally, incentivize the campus by bringing awareness of career preparation and linking it to all programming on campus, plan, and implement the change.

References

Academic Leadership Council. (2006). Guidelines for development of certificate programs at Indiana University. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University. Retrieved from: www.iu.edu

Bureau of National Affairs. (2018). Building Tomorrow’s Talent: Collaboration Can Close Emerging Skills Gap. Retrieved from http://unitedwayswva.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/Building-Tomorrows-Talent-Collaboration-Can-Close-Emerging-Skills-Gap.pdf

Capelli, P. (2012). Why good people can’t get jobs: The Skills gap and what companies can do about it (Philadelphia: Wharton Digital Press), 10.

Center for Teaching. (2020). What is service learning or community engagement. Vanderbilt University: Nashville, TN. Retrieved from: https://cft.vanderbilt.edu/guides-sub-pages/teaching-through-community-engagement/

Community College of Aurora. (2020). Retrieved from: https://www.ccaurora.edu/programs-classes/online-learning/benefits-online-education

Craig, R. (2019). America’s skills gap: Why Ii’s real, and why it matters.

Dumbauld, B. (2017). 13 Great Benefits of online learning. StraighterLine: Baltimore, MD. Retrieved from: www.straighterline.com/blog/34-top-secret-benefits-of-studying-online/

Ejiwale, J.A. (2014). Limiting skills gap effect on future graduates. Journal of Education and Learning, 8(3), 209-216.

Feffer, M. (2016). HR’s hard challenge: When employees lack soft skills. Society for Human Resource Management (SHRM). Retrieved from: https://www.shrm.org/hr-today/news/hr-magazine/0416/pages/hrs-hard-challenge-when-employees-lack-soft-skills.aspx

Field, M., Lee, R., & Field, M.L. (1994). “Assessing interdisciplinary learning.” New Directions in Teaching and Learning, 58, pp. 69-84.

Fink, L. D. (2003). Creating significant learning experiences: An integrated approach to designing college courses. San Francisco, Calif: Jossey-Bass.

Klein. J.T. (1990). Interdisciplinary: history, theory and practice. Detroit: Wayne State University Press.

Lattuca, L.R., Voigt, L.J., & Fath, K.Q., (2004). Does interdisciplinarity promote learning? Theoretical Support and Researchable Questions. The Review of Higher Education, 28, 1, pp. 23-48.

Mitcham, C. (2010). The Handbook of interdisciplinary. Oxford University Press.

National Association of Colleges & Employers (NACE). (2017). Employers rate career competencies, new hire proficiency. Retrieved from: https://www.naceweb.org/talent-acquisition/internships/employers-rate-competencies-students-career-readiness/

National Center for Education Statistics. (October 2019). IPEDS: Integrated Postsecondary \ Education Data System. Washington, D.C.

Repko, A. F. (2009). Assessing Interdisciplinary Learning Outcomes. Working Paper, School of Urban and Public Affairs, University of Texas at Arlington.

Snyder, S. (2019). “Talent, not technology, is the key to success in a digital future.” World Economic Forum. January 11, 2019. Accessed February 19, 2019. www.weforum.org/agenda/2019/01/talent-not-technology-is-the-key-to-success-in-a-digital-future/

Strauss, K. (2016). These are the skills bosses say new college grads do not have. Retrieved from www.forbes.com/sites/karstenstrauss/2016/05/17/these-are-the-skills-bosses-say-new-college-grads-do-not-have/#1cb6a2ff5491

Suny Empire State College. (2019). Guidelines for developing certificate programs procedures. Saratoga Springs, NY. Retrieved from: www.esc.edu/policies

U.S. Chamber of Commerce Foundation. (2018). Bridging the soft skills gap: How the business and education sectors are partnering to prepare students for the 21st century workforce. Retrieved from https://www.uschamberfoundation.org/sites/default/files/Bridging%20The%20Soft%20Skills%20Gap_White%20Paper%20FINAL_11.2.17%20.pdf

Wood, S. (2018). Recent graduates lack soft skills, New Study Reports. Retrieved from https://diverseeducation.com/article/121784/

Spring 2020: Critical Conversations and the Academy