Bringing Oysters Back to New York Harbor

Published in:

November 22–23, 2019

University of Miami

Miami, Florida

Abstract

Before it became the largest metropolis in the United States, New York Harbor was the greatest oyster habitat on the planet. Some estimates suggest that the islands, waterways, bays, and marshes of the Hudson and Raritan River estuaries may have been home to as much as half of the world’s oyster population. For centuries, the bountiful bivalves served as both as a dietary staple and a booming industry, providing sustenance and jobs for New Yorkers of all classes and backgrounds. But by the early 1900s, after years of overharvesting and increasing pollution, not even New York’s massive oyster population could withstand the explosive growth of the city. Local officials finally declared New York Harbor oysters unsafe to eat in 1927 and they have been functionally extinct ever since.

Just in the last decade, however, a number of environmental and educational organizations have initiated campaigns to bring oysters back to New York waters. Groups like the Billion Oyster Project, which aims to seed 1 billion oysters by the year 2050, hope that a restored oyster population will once again provide critical environmental services to the local ecosystem. This paper examines one such oyster restoration experiment conducted by undergraduate researchers at Wagner College in conjunction with the Billion Oyster Project to measure whether oysters would thrive in Lemon Creek, a marshy wetland area on the southeastern coast of Staten Island.

Bringing Oysters Back to New York Harbor

In the summer of 2016, twelve undergraduate researchers at Wagner College set out to answer a simple question: would oysters still grow in the waters surrounding New York City? Before it became the largest metropolis in the United States, New York Harbor was the greatest oyster habitat on the planet. For centuries, the bivalves occupied a central place in the city’s economy and diet–a source of jobs and a signature dish for rich and poor alike. But by the early 1900s, after years of overharvesting and increasing pollution, not even New York’s massive oyster population could withstand the explosive growth of the city. Local officials finally declared New York Harbor oysters unsafe to eat in 1927 and the bivalves have been functionally extinct ever since.

Just in the last several decades, however, a number of environmental and educational organizations have initiated campaigns to bring oysters back to New York waters. Groups like the Billion Oyster Project (BOP), which aims to seed 1 billion oysters in the harbor by the year 2050, hope that a restored oyster population will once again provide critical ecological services within the Hudson River estuary. As part of this effort, Wagner undergraduates partnered with the BOP to test whether, and how fast, juvenile oysters would grow in Lemon Creek, a marshy wetland area on the southeastern coast of Staten Island. This paper will examine the history of oysters in New York Harbor, outline the design and results of the Lemon Creek restoration study, and argue that such projects can serve as a model for mentoring interdisciplinary undergraduate research in a field critical to the future of coastal cities like New York.

The History of Oysters in New York Harbor

It can be difficult to imagine modern-day New York City–a sprawling metropolis of more than 8.5 million people–as a natural place, home to plants and animals, ecosystems, or any of the things we usually associate with nature. In fact, the approximately 300 square miles of the current five boroughs are likely one of the most developed, built up, and human-affected places in the entire Western Hemisphere. But if we turn the clock back to the year 1609, when English explorer Henry Hudson first sailed through the narrow strait between Brooklyn and Staten Island, New York Harbor looked very different. The collection of islands, rivers, bays, tidal straights, salt marshes, and rocky hills that made up the expansive estuary at the mouth of the great Hudson River system was something of an ecological treasure, home to a tremendous diversity of living things. According to ecologist Eric Sanderson (2009), if the region hadn’t grown into America’s largest city, it likely would have become a national park, on the order of a Yellowstone or a Muir Woods.

At the foundation of this thriving ecosystem, the keystone species, was Crassostrea virginica, the eastern oyster. At the moment Hudson first arrived to encounter local Lenape Indians in 1609, New York Harbor was probably the single largest oyster habitat on the planet. Something like 350 square miles of oyster beds stretched from the mouth of the harbor at southern Staten Island, up the Hudson and East Rivers, and across the salt marshes of present day Brooklyn and Queens. Recent estimates suggest that perhaps as much as half of the entire global population of oysters lived in and around the New York area (Kurlansky, 2006).

Given this kind of abundance, we shouldn’t be surprised that oysters helped to attract humans to the mouth of the Hudson River in the first place and that the bivalves became a crucial component of the local economy as the city grew. Shellfish provided a stable, reliable, and easily accessible source of food for Lenape Indians for thousands of years before Europeans ever arrived and the first Dutch settlers and the African slaves they brought with them quickly caught on. With time and room to spread, early New York oysters could live for 12 to 15 years and grow to as much as 12 inches long, a far cry from the three or four inchers common on today’s raw bars. Archaeologists have found the remains of massive shells in so-called “middens,” the planned or unplanned trash heaps left behind by settlements of Lenape, all across the present-day five boroughs (Lightfoot, 1986). One particularly impressive pile of shells in lower Manhattan inspired early Dutch colonists to bestow the name Pearl Street onto one of the city’s most important coastal thoroughfares (Kurlansky, 2006).

For the next several centuries, oysters became a full-fledged industry in New York and especially on Staten Island. At first New Yorkers gathered the bivalves by hand or using special oyster tongs, as seen in this 1853 oil painting housed at the Staten Island Historical Society.

As the city’s population swelled over the 1700s and 1800s, the demand for oysters ballooned as well. Soon oystermen graduated to more effective harvesting techniques, using massive dredges, first powered by sail and later by steam. A burgeoning industry required workers–people to bring in the catch, people to sort and process, and people to bring the product to market. In southern Staten Island, many of these workers came from Sandy Ground, one of the first and longest lasting free African-American communities in New York. Former slaves and free blacks, many of whom were recent transplants from the oystering regions of the Chesapeake, set up shop along the docks and warehouses of Princes Bay to harvest and deliver shellfish to the growing markets of the Greater New York region (Lundrigan, 2004).

What about demand? Who was eating all of these oysters pouring in from the bay? In New York, almost everyone. Before the hot dog, before the thin crust pizza, the oyster was New York’s original signature food. The wealthy slurped oysters in the city’s finest restaurants. An 1893 dinner menu from Manhattan’s Metropolitan Hotel, stored and digitized by the New York Public Library’s “What’s on the Menu?” Project, lists at least 16 separate preparations of the delicacy, including stewed oysters, fried oysters, oysters on the half shell, oysters au gratin, and more. New York’s middle and working classes also enjoyed the shellfish in open air markets, street carts, and delivered door to door by horse cart. This ca. 1840 watercolor by Italian artist Nicolino Calyo captures a street-seller at work, complete with the full complement of condiments ready at hand.

By the mid 1800s, the growing city was consuming oysters so quickly that not even the great beds of New York Harbor could keep up. Big commercial harvesting operations scoured shellfish beds until there was almost nothing left. Chemicals streaming from the city’s factories and garbage and sewage from city’s swelling population choked the harbor (Kurlansky, 2006). A remarkable map produced by the New York Pollution Commission in 1906 begins to demonstrate the nature of the problem. The mapmakers–teams of scientists and public health official–painstakingly marked the locations of more than 350 open drainpipes which emptied an estimated 455 million gallons of raw, untreated sewage into the harbor every day. They then traced how normal tidal flows washed this stinking mixture over and through the city’s many remaining shellfish beds in and outside of the direct inner harbor area (New York Public Library, 1906). By 1927, decades of increasing pollution and intensive overharvesting had taken their toll. City leaders finally declared harbor oysters unsafe to eat. The bivalves have remained functionally extinct–that is, largely unable to maintain self-sustaining populations–in New York waters ever since.

The Lemon Creek Experiment

Just in the past few decades, a variety of organizations have begun to ask if it might be possible to restore oyster populations in New York. Non-profit groups like the BOP do not seek to re-establish commercial farming or harvesting operations; harbor oysters remain unsafe for consumption, largely thanks to the city’s aging Combined Sewer Outflow (CSO) system, which still dumps raw sewage into the rivers when wastewater treatment plants are overwhelmed by surges of storm water during significant rain events. Rather, recent oyster restoration projects are intended to serve environmental and educational goals: an attempt to rehabilitate a key piece of the local aquatic ecosystem that has been missing for at least a century, and to engage various populations of local residents, students, and others in the process.

Ecologists are particularly interested in oysters because they provide three critical environmental services. First, the bivalves are natural filter feeders. An adult oyster can process as much as 50 gallons of water per day, drawing out nitrogen and other particulate matter that might otherwise contribute to oxygen-depleting algal blooms. Second, oysters are ecosystem engineers–they build habitat for other species. Just like a coral reef in tropical waters, oyster beds provide a foundation in which a great variety of other plants and animals can thrive. A healthy oyster reef can support a whole menagerie of fish, crabs, amphibians, aquatic birds, and more. Third, and maybe most importantly as sea levels rise and weather becomes more severe, oyster reefs create natural barriers that protect the shoreline from erosion and storm surges. The shellfish grow together in irregularly shaped clumps that combine into large, rough beds. When extending out from the shoreline, these reefs can help to absorb and diffuse wave energy before it reaches the shoreline (McFarland & Hare, 2018).

With these goals in mind, undergraduate researchers from Wagner College set out in 2016 to test whether, how fast, and under what conditions oysters would grow in Lemon Creek, Staten Island. Students began by carefully tagging clumps of juvenile oysters generously donated by the BOP and dividing them into 15 separate floating cage rigs. As depicted below, each of the rigs consisted of a mesh cage supported by cylindrical floats and anchored to the creek bottom by a cinder block.

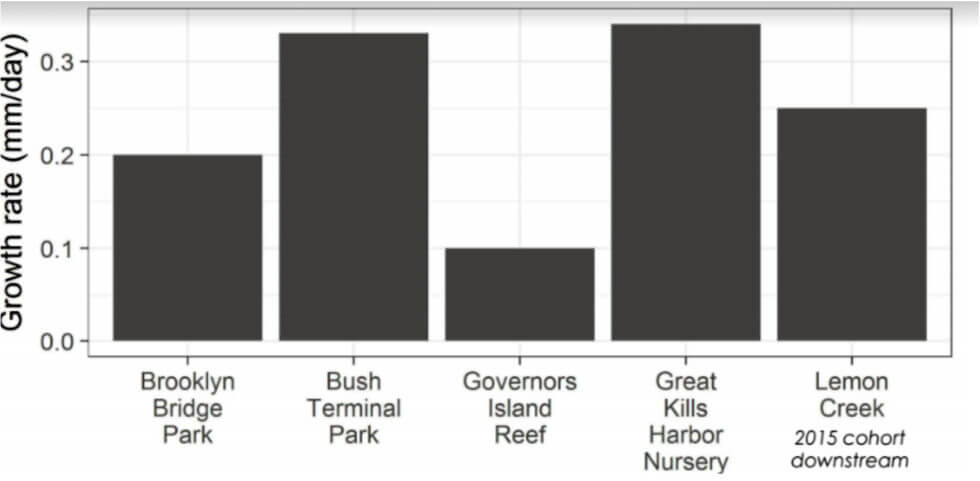

Students placed the cages at 15 different locations along the length of Lemon Creek, from the deeper, faster moving water of the creek mouth to the marshy flats of the upper creek bed. In each case, they sought to allow the floating cages to rise and fall unhindered with the tide. The undergraduate researchers then returned to Lemon Creek on four separate occasions over the next six months to measure oyster growth and survival rates. The results indicated that under the best conditions–in the faster moving tidal stream near the creek mouth–juvenile oysters grew at a rate of approximately 2.5 millimeters per day. This rate represents normal oyster development and compared favorably to growth rates at other BOP restoration sites around New York Harbor, including Brooklyn Bridge Park and Governor’s Island. Those oysters placed further upstream in Lemon Creek fared slightly worse, likely due to a lesser amount of available nutrients to filter feed in the slower moving water.

The Lemon Creek experiment represented a success not only in proving that oysters can still thrive in the coastal waters of Staten Island, but also in engaging undergraduates in interdisciplinary, hands on research. The 12 students who volunteered to participate in the various phases of the project came from a variety of academic backgrounds, including the sciences, nursing, history, and education. They absorbed new sets of facts (oyster life cycles, estuarine ecology, sustainable coastal resiliency) and developed new sets of skills (experiment design, oyster growth measurement, collation and presentation of data). And perhaps most rewardingly, they saw a direct connection between scholarly research and real-world challenges. Thanks in part to the positive results of this undergraduate study, the BOP decided to build out a much more substantial and permanent oyster nursery in Lemon Creek. This installation is not merely a feasibility test, but rather a resource intensive effort to create the critical mass of population necessary to jumpstart a self-sustaining reef. The hope is that these oysters, along with other new transplants, will help colonize the so-called Living Breakwaters Project, an ongoing $60 million effort to build breakwaters off the shore of Southeastern Staten Island (SCAPE, n.d.). Conceived in the aftermath of Hurricane Sandy, the Living Breakwaters Project will combine artificial concrete barriers with oyster reefs in order to defend the shoreline from destructive wave action, storm surges, and erosion. The ability to see a link between scholarly research and major, cutting edge, big dollar infrastructure projects designed to address the greatest environmental challenges facing coastal cities like New York proved to be a powerful experience for undergraduates and a meaningful endorsement of intellectual inquiry.

References

Billion Oyster Project. (n.d.). Our purpose. Retrieved from https://billionoysterproject.org/about/our-story/

Kurlansky, Mark (2006). The Big oyster: History on the half shell. New York, NY: Random House.

Lightfoot, Kent G. (1986). Shell midden diversity: A case example from coastal New York. North American Archaeologist, 6, 289-324.

Lionel Pincus and Princess Firyal Map Division, The New York Public Library. (1906). Outline map of New York Harbor & vicinity. Retrieved from http://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/5fd484ac-dfd8-31b5-e040-e00a18060c12

Lundrigan, Margaret. (2004). Staten Island: Isle of the bay. Charleston, SC: Arcadia Publishing.

McFarland Katherine, & Hare, Matthew P. (2018). Restoring oysters to urban estuaries: Redefining habitat quality for eastern oyster performance near New York City. PLoS ONE 13(11). Retrieved from https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0207368

Sanderson, Eric (2009). Mannahatta: A Natural history of New York City. New York, NY: Abrams Books.

SCAPE. (n.d.). Living breakwaters rebuild by design competition. Retrieved from https://www.scapestudio.com/projects/living-breakwaters-competition/

Spring 2020: Critical Conversations and the Academy