Advancing Social Justice to Support LGBTQ+ Student Mental Health and Wellness on College Campuses in a Post-COVID World

Published in:

November 19–20, 2021

Virtual Symposium

The content of this article stems from a 21-month grant from the Center for Educational Opportunity, at Albany State University, supported by the Koch Foundation, entitled, Identifying Strategies from Education-Related Activities to Provide Improved Academic Access for LGBTQIAP Students of Color. The literature clearly demonstrates that this specific population of students are at significantly greater risk because they not only identify as LGBTQ+, but are also students of color (Day, J. K., Loverno, S., & Russell, S. T., 2019; Fenaughty, J., Lucassen, M., Clark, T., & Denny, S., 2019; Hatchel, T., JR. Polanin & D. L. Espelage, 2021; Juvonen, J., Lessard, L. M., Rastogi, R., Schacter, H. L., & Smith, D. S., 2019; Mobley, S and J. Johnson, 2015 and; Paceley, M. S, 2016). Their race, gender identity, and often social class, intersect with competing priorities and varied outcomes. Colleges need to identify and address the challenges student face; affirm and empower their authentic selves; encourage coping strategies to overcome challenges; and build a nurturing and supportive culture of learning. This is true especially for LGBTQ+ students who desperately need the tools to be successful learners and to improve their own mental health and well-being, in an often less than affirming environment.

Introduction

This presentation focuses on what colleges and universities need to know in order to address the intersectional challenges experienced by LGBTQ+ college students of color to advance social justice for these students and the entire campus community. Specifically, the article will discuss: 1) How to teach tolerance, while raising awareness of difference, oppression, power, and discrimination; 2) How to address the extreme LGBTQ+ mental health crisis, including but not limited to isolation, mental health and wellness, trauma, and suicide on college campuses; and 3) How campuses can become stronger allies in creating and sustaining a truly inclusive, safe, and diverse community for all learners.

How to Teach Tolerance

According to the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (2019), 15- to 17-year-olds who identified as “non-heterosexual” rose from 8.3% to 11.7% nationwide between 2015 and 2019. Youth that identify as belonging to the LBGTQ community often are mistreated and misunderstood and experience higher rates of stress and depression than their heterosexual counterparts. These stress factors can have lifelong impact on mental, emotional, and physical health in addition to affecting academic performance. For LBGTQ youth to succeed academically, school systems should provide environments where all youth feel safe and are educated on cultural differences and cultural sensitivity.

Tolerance is defined as “the acceptance of others whose sexuality, actions, beliefs, physical capabilities, religion, customs, ethnicity, nationality, and so on differ from one’s own” (Merriam-Webster, 2020). Thirty years ago, Learning for Justice, formally known as Teaching Tolerance, was founded by the Southern Poverty Law Center. At its inception in 1991, the goal of the organization was to eradicate hate by fighting intolerance in schools. The organization developed the Social Justice Standards as a road map for anti-bias education that can be implemented at every grade level. The standards are organized into four domains: identity, diversity, justice, and action (IDJA). Together, these domains, which include corresponding grade-level outcomes and school-based scenarios, represent a varied deep dive into anti-bias, multicultural, and social justice education. The IDJA domains are based on Louise Derman-Sparks’ four goals for anti-bias education in early childhood.

The Perspectives for a Diverse America is a K-12 anti-bias curriculum developed from the principles of the Social Justice Standards framework. Educators are encouraged to integrate the free resource into their prescribed curriculum. Each activity is associated with one of the domains listed above and has an expected grade outcome. The curriculum can be found at perspectives.tolerance.org. The use of the curriculum school-wide can help explain discrimination and raise awareness of difference, oppression, and power. Educators and other school personnel have a key responsibility to create safe affirming spaces so that students can thrive, be successful, experience a high level of well-being, and mature into their full potential.

Raising Awareness of Difference, Oppression, Power, and Discrimination

Identity serves as the single most significant protective factor to assist individuals in effectively navigating the challenges and circumstances of one’s lived experience. Embracing the multiple identities, roles, and responsibilities of all individuals in a healthy manner will ensure their positive growth, maturation and development. Recognizing the multiple contexts in which identity converges for members of the LGBTQIA+ community is critical for supporting students and facilitating their embrace of the complexities of their unique identity. It has been successfully argued by Dr. Kimberlé Crenshaw (“Kimberlé,” 2017) that we must move beyond the use of a “single-axis” framework whereby one only considers a single identity (race/ethnicity), rather than multiple categories (race/ethnicity and gender and sexual orientation), in advancing understanding of how to ensure the legal protection of all equally under the law. Intersectionality (“Kimberlé,” 2017) for example, serves as the theoretical and conceptual framework developed to help explain the multiple oppressions African-American women experience. The use of the term “intersectionality” has been more broadly adopted by communities of color and by LGBTQI+ students to illustrate the breadth, impact, and complexity of the identity development experience, with special attention paid to observing “where power comes and collides, where it interlocks and intersects” (“Kimberlé,” 2017)

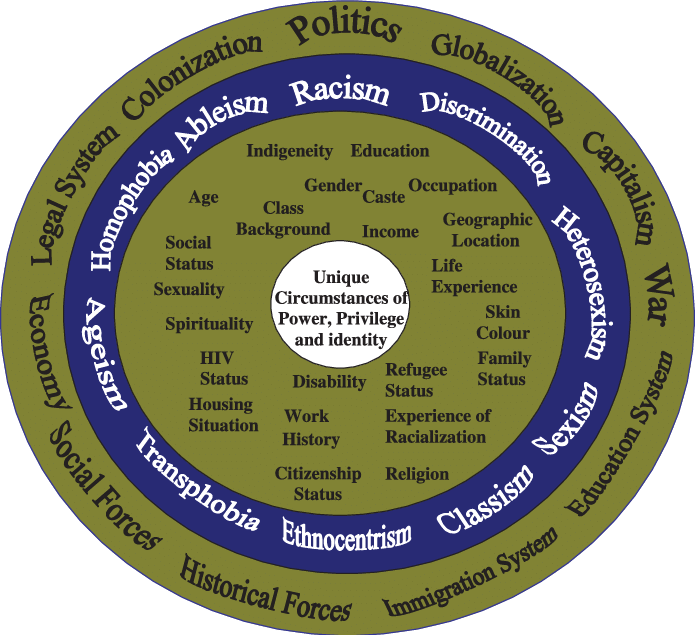

An effective model for students for visually representing and exploring the multiple ways in which they exist in the world is the intersectionality wheel (see Figure 1). It serves as a self-defining, self-naming, and agency-affirming experience to empower individuals to conceive, manifest, and advance their own vision of who they are and who they want to become. The intersectionality wheel captures overlapping or intersecting social identities and related systems of oppression, domination, and/or discrimination that unite to create significant components of identity configuration, including gender, race/ethnicity, social class, nationality, sexual orientation, religion, age, mental ability, physical ability, mental illness, physical illness, and more (Jayakumar, 2017).

Educators seeking to support students in understanding themselves as they move through their psychosocial development and mature into healthy young adults can use the intersectionality wheel to help students explore who they are (their unique qualities) and anchor that understanding within larger social-cultural systems. These systems may be exposing them to group membership discrimination, societal forces, and structural oppression.

How to Address the Extreme LGBTQ+ Mental Health Crisis

Mental health issues have risen to an all-time high as COVID-19 has taken up residence throughout the world (Holland, 2020). No human group has been exempted from feelings of isolation, abandonment, anxiety, or depression. LGBTQIA+ youth have had mental health issues prior to COVID, due to bullying, devaluation, rejection, and harmful treatment by family and others. Fortunately, various communities had safe places where LGBTQIA+ individuals could go to show their authentic selves. When COVID shut down most of the world, young people found themselves with few opportunities to connect with other youth, adults, and allies. This isolation intensified LGBTQIA+ youth’s mental health crisis, as having to stay at home increased the danger and discrimination they experienced. Living in homes with non-accepting persons further alienated the youth from self and others, increased depression, anxiety, and alcohol and drug abuse. With the safety net that homes should provide missing for LGBTQIA+ youth, many have resorted to suicide attempts with a disproportionate rate of completion among that group.

From October to December 2020, the Trevor Project collected and analyzed data from 35,000 LGBTQIA+ youth between the ages of 13 and 24. The survey found that 42% of the participants had “seriously considered” attempting suicide in the last year. This included more than half of the transgender and non-binary respondents: “Overall, more than half of the LGBTQ youth respondents reported discrimination, based on their sexual orientation or gender identity in the last year. Seventy-five percent said that this had occurred at least once in their lifetime. Only 1 in 3 LGBTQ youth said that their home was LGBTQ-affirming, and 49% of transgender and non-binary respondents reported that no one they lived with respected their pronouns” (Sandolu, 2021). The American Association of Suicidology (2019), in its The Youth Risk Behavior Survey – Data Summary & Trends Report: 2007-2017, found “LGBTQ high school students were more than four time as likely as their straight peers to have attempted suicide, and 39% of LGBTQ youth seriously considered attempting suicide in the past twelve months.” These statistics indicate the vulnerability that LBGTQ individuals continue to endure.

There are several things that can be done to support our LGBTQ youth. The first is to become an ally, especially when the voices of these young people are not being heard or when they can’t speak. Find or create safe spaces where sexual identity can be explored, understood, and accepted. Be advocates for them with their families, in their communities, and with legislators. We can encourage them to seek help prior to and when contemplating suicide. And include LGBTQ youth in decisions related to their wellbeing, which speaks to inclusiveness and equity.

How to Become Stronger Allies in Creating and Sustaining a Truly Inclusive Community

An “ally” is defined as an individual who speaks out and stands up for a person or group. Campuses can become stronger allies in creating and sustaining a truly inclusive, safe, and diverse community for all learners by following four primary steps. These include: 1) Knowing the issues; 2) Supporting LGBTQIA+ communities; 3) Educating everyone on the community; and 4) Advocating for all community members, especially LGBTQIA+ community members. These steps are critically important in order to meaningfully support the community. Some colleges encourage members of the community to take the Ally’s Safe Zone Pledge reproduced here:

- I [name] pledge to respect and value LGBTQ+ communities, histories, stories and experiences;

- To maintain confidentiality as requested by LGBTQ+ members who seek support through Safe Zone;

- To be committed to dismantling homophobia, heterosexism, and systems of oppression impacting LGBTQ+ communities;

- To continuously educate myself on and advocate with LGBTQ+ communities, and;

- To support the building of safe, supportive, and welcoming environments for LGBTQ+ communities.

The first step in becoming an ally is knowing the issues. Faculty, staff, and students can be an ally to another person in the community who they know are experiencing either verbal or physical bullying because of his, her, or their authentic selves. The ultimate goal is to provide a safe space to welcome and support lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and other students. Based on the literature (Day, J. K., et al., 2019) most college students who identify as LGBTQIA+ overwhelmingly do not feel safe on most college campuses. They often report frequently hearing anti-LGBTQIA+ language and experiencing discrimination and racism because of their sexual orientation, race, and gender expression. Many report other harassment issues both on and off campus. This research study also indicates that when students feel safe, they are more likely to earn better grades and proceed more consistently towards graduation.

Oftentimes, allies have come to better understand their own beliefs, and even test their own understanding and knowledge of inclusive language, by staying abreast of the issues relating to and of the methods for fighting anti-LGBTQIA+ discrimination. Knowing the issues provides allies with the ability to reduce oppression and advocate for all persons who are stigmatized, discriminated against, or treated unfairly. When standing up for the rights of LGBTQIA+ individuals, faculty members demonstrate to students that they are not alone. This is key to nurturing a supportive school climate and reduces the chances of an individual not feeling safe within the campus environment. Because we know that LGBTQIA+ students of color are of greatest risk of being bullied and targeted unfairly, and that this puts them at greater risk of hostile behavior of others, advocating for them and respectfully accepting their identity by using proper language can make a huge, lasting difference. When a person’s identity is not respected, it can create a hostile environment, great discomfort, and anxiety, and can encourage target individuals perceived as being LGBTQIA+ to remain silent.

Research indicates (Trevor Project, 2021) that a supportive college staff has a positive impact on the entire student experience. They often interact more closely with college students, specifically in the counseling, academic, dormitory and student affairs departments. This makes their reach greater, because of the consistency and depth of their student interactions, which can lead to a much greater number of LGBTQIA+ students feeling safer and to a more positive successful living and learning environment.

The second step is meaningfully supporting LGBTQIA+ communities. Some college community members often report that they want to be supportive but don’t know how. The four main ways you can be supportive are to be a visible ally both in your actions and in your professional space. For example, you may have a “Safe Space” poster on your door or in your classroom, or other welcoming messaging for the LGBTQIA+ community clearly visible in your office. Counselors can provide materials to place outside your door. Research shows that even if LGBTQIA+ students know that they have supportive educators, seeing these messages will make them feel better about being in school. Second, you can provide support to students who come out to you. Even if you are not sure what to do, you can inform yourself, seek resources both for you to advocate better and to direct the student to obtain professional and personal assistance through this challenging period in their lives. Third, you can consistently respond to anti-LGBTQIA+ language and behaviors in school, whenever and wherever you encounter discriminatory situations. In addition, it is important to let other colleagues know about the fact that you support the LGBTQIA+ community and that you do provide a safe space for conversations, engagement, and resources. Another source of support is simply being a good listener. You can show students that you understand and that they can count on you showing up for them when you demonstrate knowledge of anti-LGBTQIA+ behaviors and actions against them and others. And fourth, you can support student clubs, such as Gay-Straight Alliances or any inclusive student organization that serves to support LGBTQIA+ and other students facing hostile environments based, primarily, on one’s sexual orientation or gender identity or expression.

Intentionally using inclusive language in all places and spaces, especially in the classroom and around other students, is extremely important and shows your awareness and respect for their authentic selves. This will help them to know that you are a person who is there for their best interests. Participants attending this FRN session received a toolkit of inclusive resources to gain a better appreciation of how to maximize support for LGBTQIA+ students and how to address some of their most pressing needs.

The third step is educating everyone in the college community. This begins with teaching all members of the community to respect and engage with one another throughout the campus community. This encourages awareness and growth of persons who may be different from ourselves and a greater appreciation for difference. The more engagement among all campus community members, inside and outside of classes, the greater the opportunity for meaningful dialogue and interaction. Also important is ensuring that the curriculum is LGBTQ+ inclusive, possibly by fostering awareness of the history of the persecution of gay and lesbian members of society. This should not only be done during PRIDE month in June, but also throughout the year. Furthermore, all members of the campus community should participate in activities that advocate for positive change and that increase appreciation for all members of the community. Everyone in the community also should understand how to respond to anti-LGBTQ+ behaviors and actions. Whatever the situation, faculty, staff, and students need to clearly understand what is happening and how they can be supportive of each other. Many of these incidents go unreported because of fear of retaliation, perceived lack of support, and unwillingness of others to believe and stand up for targets of anti-LGBTQ+ behavior. The more visible and greater the number of allies, the less likely these incidents will continue. For faculty and staff, seminars, webinars, and other types of professional development can be provided to offer training and development.

The fourth and final step of an ally is advocating for all, especially members of the LGBTQ+ community. A key role of an ally is to use the power and influence they have as an educator to advocate for the rights of LGBTQ+ students and ensure safe campuses for all community members. Typically, there are three measures that a college can take, beginning with an assessment of your college’s climate, policies, and practices. This assessment demonstrates how members view the campus environment, climate, and culture by asking about their experiences in the college community. It identifies areas for improvement by reviewing the college’s policies and practices for ensuring that the school is safe and inclusive with regards to campus events, course content, and co-curricular activities. Assessment may lead to the implementation of comprehensive anti-bullying and anti-harassment practices, as well as the initiation of programs and services that affirm and support safety, and provide a better climate for all college members. The final component is the encouragement of nondiscriminatory practices to eliminate the homophobia or transphobia that often manifest themselves in campus policies and practices. While some may be resistant to this change, they need to understand that, left uncorrected, these college policies and practices often serve to create a hostile environment filled with all types of discrimination against LGBTQ+ students. Some possible solutions include providing gender-neutral bathrooms, ensuring that college events are inclusive of same-sex couples, and acquiring multicultural literature in the library that includes all people, including LGBTQ+ individuals and their history. Another is to be cognizant that while the college secures the internet filters from cyberattacks, it does not unintentionally block students from finding positive and helpful information about the LGBTQ+ community.

In summary, a good action plan for college campuses is to support, educate, advocate for, and provide generous resources and information to your college community that intentionally engage and impact that community. Colleges need to identify and address the challenges that students face, affirm and empower their authentic selves, encourage coping strategies to overcome challenges, and build a nurturing and supportive culture of learning, especially for LGBTQ+ students who desperately need the tools and empowerment to be successful learners and to improve their own mental health and well-being, in an often less than affirming environment.

“Harmony,” a song by an aspiring, African American, questioning young woman, Courtney Gregory Jones, provides some timely insight on the issues this articles addresses. Jones wrote these lyrics in 2011, at the tender age of 15, and was asked by Peter Yarrow, of the civil and human rights group Peter, Paul and Mary, to perform the song in front of an international conference audience.

Harmony

by Courtney Gregory JonesHow many kids will die, for you to hear me out?

How many times will I see this, before you try to shut my mouth?

How many times will I say this, before you start to feel ashamed?

What will it take, to get this through your brain?Cause there’s a path we all follow.

There’s a day we’ll soon claim.

But will it be something we’re proud of,

Or will we be ashamed.

Because I can’t change you.

You surely can’t change me.

Oh, but I pray, we’ll soon live in harmony.Cause there’s a path we all follow.

There’s a day we’ll soon claim.

But will it be something we’re proud of,

Or will we be ashamed.

Cause I can’t change you.

You surely can’t change me.

Oh, but I pray, that we’ll soon live in harmony.

At the conclusion of this FRN session, a toolkit was distributed to participants that included implementable strategies to assist LGBTQ+ students to build self-esteem and self-efficacy to address the increased mental health and wellness needs of college students. It also provided tools for college faculty and staff to build the collective courage to critically self-reflect, to foster critical conversations, and to commit to becoming stronger allies. These tools are included in the references below.

Acknowledgements

The research for this article was supported by a grant from the Center for Education Opportunity, Albany State University, through the Koch Foundation.

Tremendous recognition and gratitude to the members of the LGBTQ+ Advisory Council who collaborated on this grant and dedicated their time and talents to the multiple objectives of this important labor of love. Members that are not co-authors of this publication include William Britto, Chris Lugo, Rasheed Merrell, Sharina Neal, and Drs. Frank Ortega, Arika Wadley, and Eunhui Yoon. A special thank you to supportive members of the Clark Atlanta University community including, Mrs. Betty Cooke, Drs. Barbara Hill, Karis Clarke, Charmayne Patterson, Mary Hooper, Daniel Teodorescu and Dean. J. Fidel Turner. And to my beloved and talented daughter Courtney Gregory Jones who provided the initial inspiration for my passion for this tremendously important work.

References

Ally’s Safe Zone Pledge. https://continuumofcare513.com/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/Safe-Zone-Pledge.pdf

American Association of Suicidology. (2019). Suicidal behavior among lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender youth fact sheet. https://suicidology.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/Updated-LGBT-Fact-Sheet.pdf

Cohen, L. (2021, May 19) Staying home helped keep kids safe from COVID-19. But it put LGBTQ youth in a different kind of danger. CBSNews.com. https://www.cbsnews.com/news/lgbtq-youth-safety-COVID-pandemic/

Learning for Justice. Social Justice Standards. https://www.learningforjustice.org/frameworks/social-justice-standards

Crenshaw, K. (2017). On intersectionality: Essential writings. The New Press.

Day, J. K., Ioverno, S., & Russell, S. T. (2019). Safe and supportive schools for LGBT youth: Addressing educational inequities through inclusive policies and practices. Journal of school psychology, 74, 29–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2019.05.007 Gay City. Seattle Youth LBGTQ Center. Gay City: Seattle’s LGBTQ Center promotes protective factors that support the development and self-determination of LGBTQ youth.

Hatchel, T., JR. Polanin & DL. Espelage (2021) Suicidal Thoughts and Behaviors Among LGBTQ Youth: Meta-Analyses and a Systematic Review, Archives of Suicide Research, 25:1, 1-37, DOI: 10.1080/13811118.2019.1663329

Holland, Kimberly. (2020, May 7). What COVID-19 Is Doing to Our Mental Health. https://www.healthline.com/health-news/what-covid-19-is-doing-to-our-mental-health

Intersectionality wheel. Retrieved from https://www.researchgate.net/figure/ntersectionality-wheel-Simpson-2009_fig1_301674339

Jayakumar, K. (2017, October 12). Understanding Intersectionality. Retrieved from Understanding Intersectionality

Jones, C. J. (2013). Harmony.

Juvonen, J., Lessard, L. M., Rastogi, R., Schacter, H. L., & Smith, D. S. (2019). Promoting social inclusion in educational settings: Challenges and opportunities. Educational Psychologist, 54(4), 250–270. https://doi.org/10.1080/00461520.2019.1655645

Kimberlé Crenshaw on intersectionality, more than two decades later. (2017, June 8). Columbia Law School. https://www.law.columbia.edu/news/archive/kimberle-crenshaw-intersectionality-more-two-decades-later

LGBT Youth | Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender Health (2020), https://www.cdc.gov.lgbthealth.youth

Mental Health America Webinars, (May 25, 2021), Young Mental Health Leaders Series: LGBTQ Youth Mental Health Video https://www.bing.com/videos/search?q=video+wellness+activities+for+LBGTQ+youth&&view=detail&mid=5CFDA3729D6F92C8749A5CFDA3729D6F92C8749A&&FORM=VDRVSR

Paceley, M. S. (2016). Gender and sexual minority youth in nonmetropolitan communities: Individual- and community-level needs for support. Families in Society, 97(2), 77–85. https://doi.org/10.1606/1044-3894.2016.97.11

Proctoe. (n.d.). Intersectionality and school psychology: Implications for practice. National Association of School Psychologists (NASP). Retrieved February 4, 2022, from https://www.nasponline.org/resources-and-publications/resources-and-podcasts/diversity-and-social-justice/social-justice/intersectionality-and-school-psychology-implications-for-practice

Mobley, S and J. Johnson. (2015). The Role of HBCUs in Addressing the Unique Needs of LGBT Students. New Directions for Higher Education, 170, 79-89.

https://doi.org/10.1002/he.20133

Sandolu, Ana. LGBTQ youth mental health: Trevor Project survey highlights disparities. (May 19, 2021) https://www.medicalnewstoday.com/articles/lgbtq-youth-mental-health-trevor-project-survey-highlights-disparities

Sheafor, Bradford; Horejsi, Charles. (2014). Techniques and Guidelines for Social Work Practice. New Jersey: Pearson, pp 23-27.

Meriam-Webster. (2020). Tolerance. In Merriam-Webster.com. Retrieved January 28, 2022, from https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/tolerance

Trevor Project. Implications of COVID-19 for LBGTQ Youth and Mental Health, The Trevor Project Website. Site that provides information on sexual Orientation, Talking About Suicide, Mental Health, Community and Gender Identity.

Trevor Project, HERE PSA to Support LGBTQ Youth Featuring Ben Platt (June 4, 2021). Wellness Link Created Martin et al. (June 2020). Produced by several faculty from HBCU’s at Faculty Resource Network online.

Spring 2022: Redesigning Higher Education After COVID-19