Engaging Minority High School Students with Disabilities in a College Inclusion Person-Centered Planning Initiative

Published in:

November 16–17, 2012

Dillard University and Xavier University of Louisiana

New Orleans, Louisiana

Introduction

A pilot postsecondary educational initiative for individuals with cognitive disabilities is being conducted in the Seidenberg School of Computer Science and Information Systems at Pace University. Features of the initiative for high school students and young adults with developmental and intellectual disabilities, including autism, enable engagement in learning and in recreation and sociality of these individuals with peer students without disabilities (Papay & Bambara, 2011). Literature indicates that autism is affecting 1 in 110 young individuals in America (Diament, 2012); that young African-American individuals are four times more likely than Anglo-American individuals to be afflicted with developmental and intellectual disabilities (Centers for Disease Control, 1990), such as autism, but less likely than young Anglo-American individuals to be identified with disabilities (Rice, 2012); and that minorities with these disabilities have inadequate instruction (Brown, 2012) and limited public and social services (Wilson & Senices, 2005), in contrast to non-minorities without disabilities (Belgrave & Walker, 1991). Young individuals with developmental and intellectual disabilities often develop in environments that are limiting in experiences and interactions with other students without disabilities (Rousso & Wehmeyer, 2001) and that are less likely to lead to enrollment in postsecondary institutions. This paper introduces an inclusion initiative that is inherently part of a movement (Ferguson, 2012) to increase the self-advocacy of all high school students and young adults–minorities and non-minorities with cognitive disabilities and without disabilities.

Learning Program in Seidenberg School

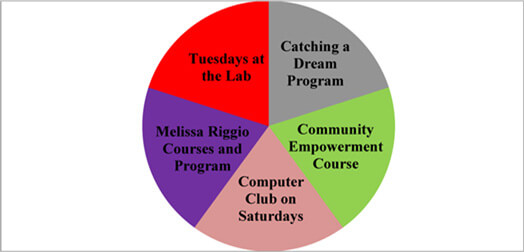

The primary focus of the pilot initiative in the Seidenberg School is an inclusion learning program for high school students and young adults with cognitive disabilities at AHRC New York City, an agency for helping individuals with developmental and intellectual disabilities. The initiative includes programs for non-credit engagement, as depicted in Figure 1. The initiative is focused on the formulation of life planning and practical skills (Paiewonsky, Mecca, Daniels, Katz, Nash, Hanson, & Gragoudas, 2010) for inclusion of the individuals in mainstream society.

Highlights of Learning Program in Seidenberg School

Catching a Dream Program

In this foundational program, higher-functioning (i.e. less impaired) high school students with developmental and intellectual disabilities are mentored by disability-sensitive undergraduate students without disabilities in the Seidenberg School. This program is focused on the preparation of person-centered dreams and hopes (generally concerning employment) by the high school students with the undergraduate students. The high school students are mentored by the undergraduate students on intermediate computer science, life planning, personal productivity, presentation and self-advocacy and social skills. The students meet each Friday for three hours in a semester of fourteen weeks at the campus of the university. The results of this program are that the high school students with disabilities have improved learning and social skills (InfoBrief, 2012) and are able to interact better with others in school and in society.

Community Empowerment Course

In this program, high school students and young adults with developmental and intellectual disabilities are mentored by other disability-sensitive undergraduate students in a community engagement course of the school. This program is focused, like the Catching a Dream Program, on the preparation and presentation of person-centered plans (Holburn, Gordon, & Vietze, 2007) by the students through multimedia narratives (Grove, 2007) with visual storytelling technologies (Dow, 2012). The high school students are mentored by the undergraduate students on life planning, presentation and self-advocacy and self-confidence skills. These individuals may be even mentored with assistive iPad services and specialized tablet tools (Stokes, 2012) if they are not verbal in initiating vocalization (Grove, 2005). The students meet each Tuesday for two hours in a semester of fourteen weeks at the campus classrooms of the university. In the last week of the program, students present their work to their families and the nonprofit organizational staff. As a result of this program, the high school students and the young adults with disabilities have improved pride and sociality skills (Eisenhauer, 2012) in order to interact with others in society, and the undergraduate students have heightened sensitivity skills to the potential of these individuals with disabilities (Danforth, 2001) to be productive in society.

(This program is concurrently focused on the presentations of visual storytelling by mid-aged to old-aged individuals with developmental and intellectual disabilities on each Thursday for two hours of the semester with even other undergraduate students.)

Computer Club on Saturdays

In this program of the initiative, young adults with developmental and intellectual disabilities are mentored by undergraduate students at the computer labs. This program is focused on the preparation of independent literacy skills. The young adults are mentored by the undergraduate students on basic computer, fundamental internet, and intermediate Microsoft skills. These students meet each Saturday for five hours in an alternating semester of nine weeks at the labs of the university, and the results are that these young adults with disabilities have increased marketable skills to be productive in society.

Melissa Riggio Courses and Program

In this program, a defined number of young adults with disabilities, effectively eligible from the New York State Office for People with Developmental and Intellectual Disabilities (OPWDD) and having a high school individualized education plan (IEP), are enrolled as noncredit and unofficial students in fundamental and intermediate courses in the Seidenberg School like other official students without disabilities.

The administrator-author, faculty members, and nonprofit organizational staff members enroll the young adults from person-centered plans (Weir, 2011) in the appropriate coursework, for example, community empowerment through technology, introduction to computer technology, multimedia technologies, software technologies and social media networking technologies.

This program is focused on increased preparation of problem solving and productivity skills through prerequisite projects of the courses, as these young adults interact with students without disabilities. Free from disruptive disorders, the young adults are intensely mentored by disability-sensitive junior and senior undergraduate students (Balcazar, Davies, Viggers, & Tranter, 2006) and the nonprofit organizational paraprofessional staff, as they perform projects in the courses of one six-hour day each week in the semester of fourteen weeks at the campus classrooms and labs of the university. The undergraduate students are essentially personal tutors to the young adults (Britner, Balcazar, Blechman, Blinn-Pike, & Larose, 2006). The metrics of the courses are not lowered by the faculty for these young adults. The results of this program are that these young adults have marketable practical skills with pronounced self-advocacy skills, and the undergraduate students have personalized sensitivity skills to the success of these young adults.

Tuesdays at the Lab

The final program of the initiative is one in which other young adults with developmental and intellectual disabilities are mentored similarly by undergraduate students in the labs. This program is focused on the preparation of marketable skills. These young adults are mentored by the students on computer literacy, fundamental internet, intermediate Microsoft, personal finance and resume tools. They meet each Tuesday for three hours in the semester of fourteen weeks in the labs of the university, and the results of this program are that they have marketable positional skills to transition into vocations.

Summary of the Learning Program at the Seidenberg School

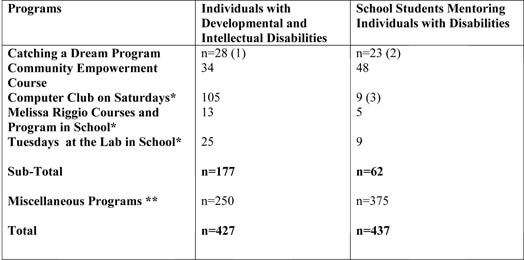

Since 2008, 177 high school students and young adults with developmental and intellectual disabilities, and 62 undergraduate student mentors, have participated in the inclusive learning person-centered planning programs; and 427 high school students, young adults, mid-aged adults, and old-aged adults with disabilities, and 437 undergraduate students, have participated in the overall programs of the initiative of the Seidenberg School, as detailed in Table 1.

*High School Students and Young Adults; **Largely Mid-Aged and Old-Aged Adults (1) Pilot of 28 in Course of 34; (2) Pilot of 23 in Miscellaneous Programs of 375; (3) Club of 9 in Lab of 9

Programs of Recreation and Sociality at the Seidenberg School

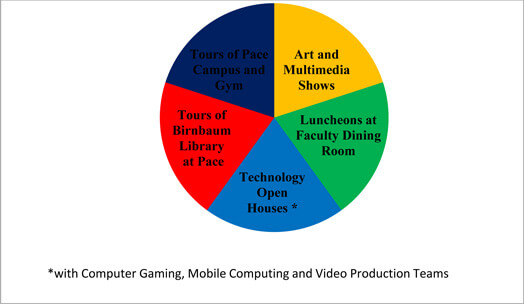

The secondary focus of the pilot initiative in the Seidenberg School is an inclusion program of recreation and sociality for the high school students and young adults with developmental and intellectual disabilities. The initiative includes multiple peer socialization with other students without disabilities, as highlighted in Figure 2. The initiative is further inclusive in popular programs in the Seidenberg School, involving the individuals with other undergraduate students in socialization, through computer gaming, mobile computing and video production teams. The high school students and the young adults are matched to the programs of socialization by the mentoring undergraduate students who participate with them. These programs in the school and in the university are focused on the integration of social skills with the aforementioned learning program skills, resulting in programs that facilitate full future inclusiveness of these students and young adults in society.

Initiative Summary

The postsecondary initiative in the Seidenberg School is clearly furnishing benefits to the AHRC New York City nonprofit organization that may be lacking monetary resources; to the high school students and the young adults with developmental and intellectual disabilities who may be lacking perceptions of self-respect (Harris, Taiping, Markle, & Wessel, 2011); and to the undergraduate students of the university learning about both the problems of a marginal population of society (National Organization on Disability, 2004) and the potential of productivity and self-advocacy solutions through technologies (Jones, Weir, & Hart, 2011).

Key Lessons Learned

Based on the experience of the author on the postsecondary initiative in the Seidenberg School, here are some of the elements that made this initiative successful. Faculty at other institutions may find that the following suggestions beneficial in pioneering a similar initiative:

- Commitment of institution to both diversity and inclusion of individuals with disabilities is clearly defined in mission statement of metropolitan university;

- Commitment of provost, dean of one school and chair of one department in the school of university is critical for an inclusion pilot initiative for individuals with developmental and intellectual disabilities;

- Concept of pilot is developed by an activist administrative faculty member and capable and compassionate faculty members, in partnership with the nonprofit organization, for a limited number of eligible higher-functioning (i.e. less impaired/low support) and highly-motivated individuals with individualized education plans (IEP), in a limited number of non-credit courses in the localized school, covered by insurance of liability, and is further insuring full nonprofit organizational readiness and responsiveness (“skin in the game”);

- Design of pilot is initiated in person-centered plans of the individuals linked to existing learning outcomes of general education program or specialized education program syllabi and matched to employment vocations that may be provided in part-time internships through the nonprofit organization or university;

- Design of pilot is initiated with disability-sensitive self-motivated students partnered with the individuals in the semesters;

- Design of pilot is initiated with the individuals so that they are in courses of pilot together with students without disabilities (“inclusion [not exclusion] is the name of the game”);

- Design of pilot is integrated into programs of recreation and socialization, so that the individuals experience life and reciprocal socialization in the university with students without disabilities;

- Inclusive infrastructural services and inclusive instructional services for faculty are furnished by internal Office of Disability Services and peripheral staff if needed by faculty, and special technologies and tools for the individuals are furnished by the school if needed by the individuals;

- Progress is reviewed by the administrative faculty member with faculty members, mentoring undergraduate students and nonprofit organizational paraprofessional staff at mid-term and final semesters if not monthly through reflective reporting; and

- If pilot progress is proven, funding for post pilot resources for the school, and for other schools of the university, is planned from Pell Grants and Postsecondary Programs for Students with Intellectual Disabilities (TPSID) Grants, through the internal Office of Financial Aid for Students in the university.

The lessons learned by the author, from experience in the school and from field research, furnish a feasible foundational methodology for pioneering an inclusive postsecondary educational initiative for high school students and young adults with developmental and intellectual disabilities.

Conclusion

The pilot postsecondary educational initiative of the Seidenberg School of Computer Science and Information Systems of Pace University is helping high school students and young adults with disabilities in learning and in recreation and socialization at the university. The initiative increases these individuals’ practical and self-advocacy skills. At the same time, this initiative is improving the sensitivity to service of the undergraduate students without disabilities that are mentoring and tutoring these individuals. The lessons learned from this workshop will be helpful to institutions considering pioneering in educational programs of inclusiveness for high school students and young adults–minorities and non-minorities–with developmental and intellectual disabilities. This workshop is relevant to instructors evaluating postsecondary programs for those who are marginalized in society.

Acknowledgements

The author acknowledges funding from grants of the AHRC New York City Education Services Foundation for mentoring stipends to the undergraduate students of Pace University in the Catching a Dream Program of the initiative and funding from grants of the Center for Teaching, Learning and Technology of the university for project technologies of the initiative.

References

Balcazar, F.E., Davies, G.L., Viggers, D., & Tranter, G. (2006). Goal attainment scaling as an effective strategy to assess the outcomes of mentoring programs for troubled youth. The International Journal on School Disaffection, 4, 43-52.

Belgrave, F.Z., & Walker, S. (1991). Predictors of employment outcome of Black persons with disabilities. Rehabilitation Psychology, 36, 111-119.

Britner, P.A., Balcazar, F.E., Blechman, E.A., Blinn-Pike, L., & Larose, S. (2006). Mentoring special youth populations. Journal of Community Psychology, 34(6), 749.

Brown, W. (n.d.). Disparities among African-Americans with autism and other disabilities. Child-Autism-Parent-Café, 1-3. Retrieved October 5, 2012 from http://www.child-autism-parent-cafe.com/

Centers for Disease Control (n.d.). Metropolitan Atlanta Development Disabilities Study (MADDS). Retrieved from http://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/developmentaldisabilities/MADDS.html

Danforth, S. (2001). A Deweyan perspective on democracy and inquiry in the field of special education. Journal of the Association for Persons with Severe Handicaps, 26(4), 270-280.

Diament, M. (2011, November 4). Minorities show more severe signs of autism. Disability Scoop. Retrieved from http://www.disabilityscoop.com/2011/11/04/jobs-october-2011/14382/

Dow, L. (2012, March 20). Visual storytelling. Social Media Today. Retrieved from http://socialmediatoday.com/leighdow/473556/visual-storytelling

Eisenhauer, J. (2010). Writing Dora: Creating community through autobiographical zines about mental illness. Journal of Cultural Research in Art Education, 28, 25-38.

Ferguson, R.F. (2012, October 23). Toward excellence with equity: An emerging vision for closing the achievement gap. Distinguished Educator Lecture, Pace University School of Education, Pleasantville, New York.

Grove, N. (2005). Ways into literature. London: David Fulton.

Grove, N. (2007). Exploring the absence of high points in story reminiscence with carers of people with profound disabilities. Journal of Policy and Practice in Intellectual Disabilities, 4(4), 252-260.

Harris, J., Taiping, H., Markle, L., & Wessel, R. (2011). Ball State University’s faculty mentorship program: Enhancing the first-year experience for students with disabilities. About Campus, 16(2), 27-29.

Holburn, S., Gordon, A., & Vietze, P.M. (2007). Person-centered planning made easy: The picture method Baltimore, Maryland: Brookes Publishing Company.

Jones, M., Weir, C., & Hart, D. (2011). Impact on Teacher Education Programs of Students with Intellectual Disabilities Attending College. Think College Insight Brief, 6. Boston, MA: University of Massachusetts Boston, Institute for Community Inclusion.

National Collaborative on Workforce and Disability for Youth (2012, February). Helping youth build work skills for job success: Tips for parents and families. InfoBrief, 12, Retrieved from http://www.pacer.org/publications/parentbriefs/InfoBrief_Feb2012_Issue34.pdf

National Organization on Disability (2004, December 15). Landmark disability survey finds pervasive disadvantages. Retrieved from http://nod.org/research_publications/surveys/harris

Paiewonsky, M., Mecca, K., Daniels, T., Katz, C., Nash, J. ,Hanson, T., & Gragoudas, S. (2010). Students and educational coaches: Developing a support plan for college. Think College Insight Brief, 4. Boston, MA: University of Massachusetts Boston, Institute for Community Inclusion.

Papay, C.K., & Bambara, L.M. (2011). Postsecondary education for transition-age students with intellectual and other developmental disabilities: A national survey. Education & Training in Autism & Developmental Disabilities, 46(1), 78-93.

Rice, C. (2011). Late diagnosis: Autism in minority communities. Minority Nurse. Retrieved from October 12, 2012 from http://www.minoritynurse.com/late-diagnosis-autism-minority-communities

Rousso, H., & Wehmeyer, M. (2001). Double jeopardy: Addressing the gender equity in special education. Albany, New York: State University of New York Press.

Stokes, S. (n.d.). Assistive technology for children with autism. Child-Autism-Parent-Café. Retrieved on October 5, 2012 from http://www.child-autism-parent-cafe.com/assistive-technology-for-children-with-autism.html

Weir, C. (2011). Using individual supports to customize a postsecondary education experience. Impact Newsletter, 23(3), 18-19. Retrieved from a href=”http://20.132.48.254/PDFS/ED516361.pdf”>http://20.132.48.254/PDFS/ED516361.pdf

Wilson, K.B., & Senices, J. (2005). Exploring the vocational rehabilitation acceptance rates of Hispanics and non-Hispanics in the United States. Journal of Counseling and Development, 83(1), 86-96.

Spring 2013: New Faces, New Expectations